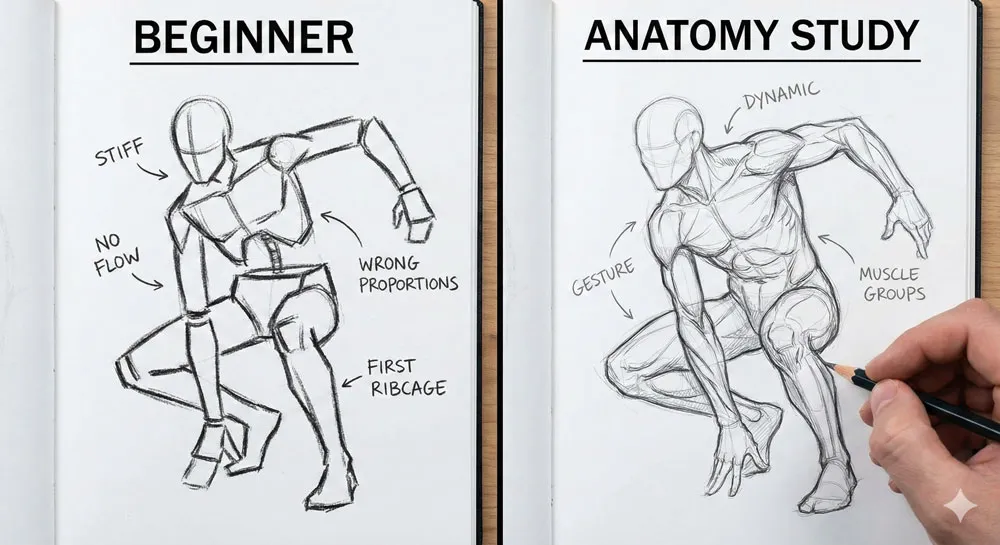

Drawing the human body might seem intimidating at first, but the truth is this: anatomy is learnable, not a talent. Whether you’re an aspiring animator, digital artist, or illustrator, understanding human anatomy is the foundation that separates amateur sketches from professional artwork.

This comprehensive guide breaks down human anatomy into simple, digestible steps specifically designed for complete beginners—no prior drawing experience required. By the end of this tutorial, you’ll understand the fundamental structure of the human body and be able to construct proportional figures from any angle.

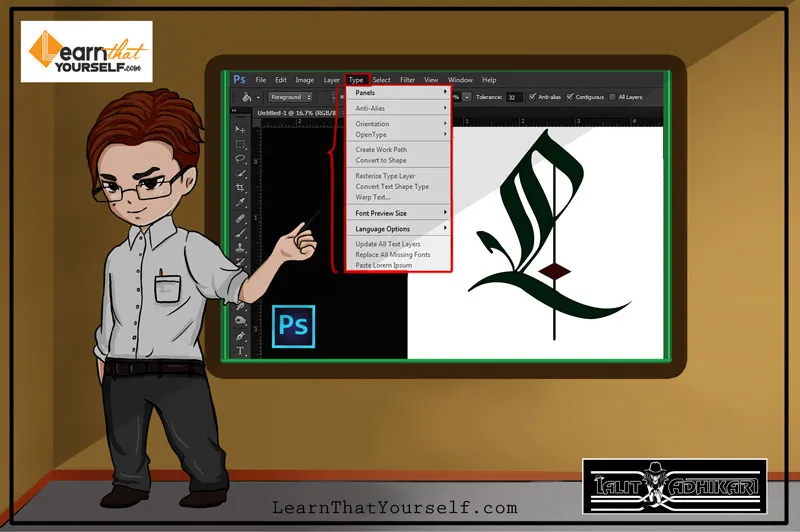

My name is Lalit Adhikari and we are at LTY. Let’s begin!

Table of Contents

Why Learn Human Anatomy? (And Why It Actually Matters)

Here’s the honest truth: you can learn to draw without understanding anatomy, but your drawings will always feel “off.”

Beginners often create figures that look stiff, proportionally broken, or lifeless—and it’s almost always because they’re drawing what they think they see instead of what’s actually there.

When you understand anatomy, you gain three superpowers

- You draw confident figures – Instead of hesitantly erasing and redrawing, you construct your figure with purpose because you know why things go where they go.

- You can draw from imagination – You’re no longer dependent on references. You understand the underlying structure, so you can pose figures in any position, any angle, from pure imagination.

- Your style develops faster – Understanding structure is what separates amateurs from professionals. Every professional animator, character designer, and illustrator learned anatomy first, then developed their own style on top of that foundation.

This matters because anatomy is not an optional skill—it’s the core competency that everything else builds on. Without it, you’re constantly fighting against your own drawings.

What is Anatomy in Art? (Remove the Mystery)

Anatomy in art is simple: it’s understanding how the human body is built so you can draw it accurately.

The word “anatomy” comes from Greek: “ana” (up) and “tome” (cutting). Medical students learn anatomy by dissecting cadavers. You don’t need to do that—but you do need to understand what’s underneath the skin: the bones, muscles, and how they connect.

Animation Drawing Vs. Illustration Drawing

Animation drawings are exclusively based on the imagination of the artist whereas Illustration drawings are created using models or photographs.

The analytical and visualization skills of the artist are polished in animation drawings whereas the observation skills of the artist are put to use in illustration drawings. It develops the ability to copy a model and present it using different techniques.

Animation drawings are a collective work of various artists. They attract attention in totality. Whereas illustration drawings are generally the work of an individual artist. It attracts attention as an individual style.

Here’s what you actually need to know

- It’s not about memorizing Latin names – You don’t need to know that the “rectus femoris” is the quadriceps. You just need to know that the thigh has a muscle group that creates a specific visual shape.

- It’s about understanding shapes and proportions – Anatomy teaches you where things connect, how they overlap, and what shapes they create on the surface.

- It’s the bridge between what you see and what you draw – When you understand anatomy, you can simplify complex shapes into basic forms, which is how every professional artist draws.

Think of anatomy as the “skeleton” of your art skills. You wouldn’t build a house without understanding where the foundation, walls, and roof go. Same concept with drawing figures.

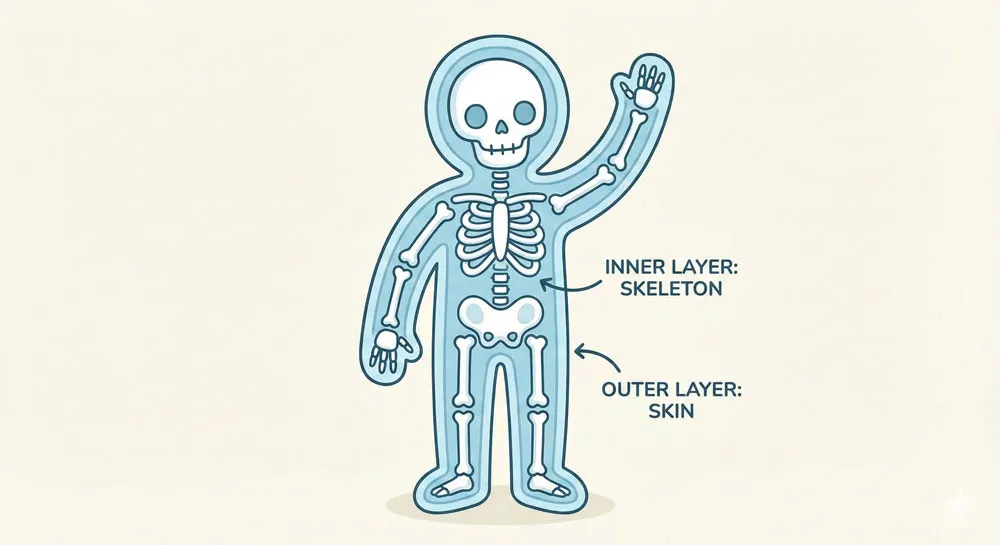

The Three Layers: Skeleton, Muscles & Skin

Every human body has three fundamental layers. Understanding these layers is the secret to drawing realistic human figures. Think of it like an architectural blueprint—you construct from the inside out.

Layer 1: The Skeleton (Your Framework)

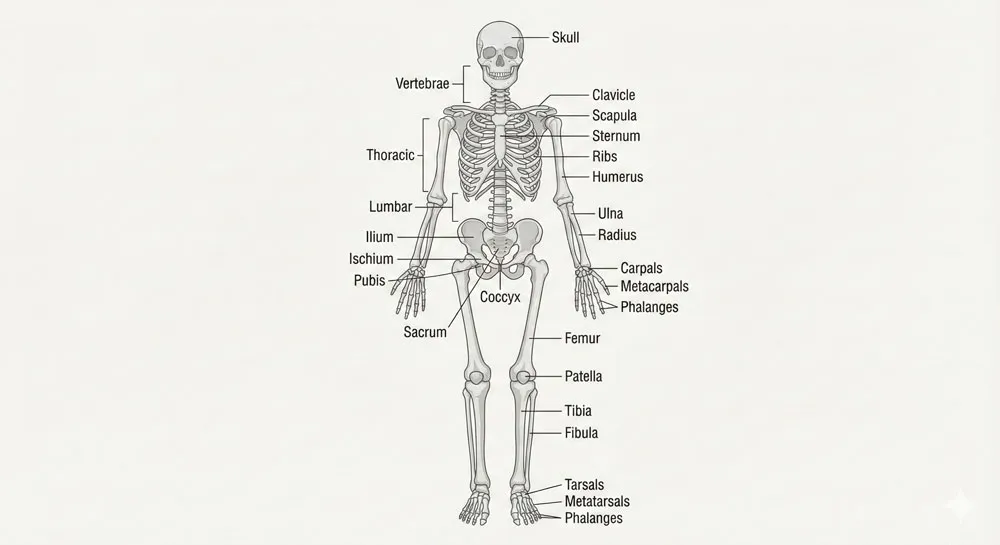

The skeleton is the armature—the core structure that gives your figure shape. It consists of bones and joints that create the overall silhouette and proportions of the body.

Why this matters for drawing: When you start a figure, you’re not drawing a realistic skeleton. You’re drawing a simplified skeleton—basic shapes and lines that represent where bones are positioned. This construction method prevents your drawings from looking disproportionate.

Key bones you should understand:

- The skull – Contains the head shape

- The rib cage – Defines the torso width and depth

- The pelvis – Creates the hip width and stance

- The spine – Connects everything and determines posture

- Long bones of limbs – Determine arm and leg proportions

The skeleton isn’t a detailed medical illustration—it’s a simplified framework that you’ll build upon.

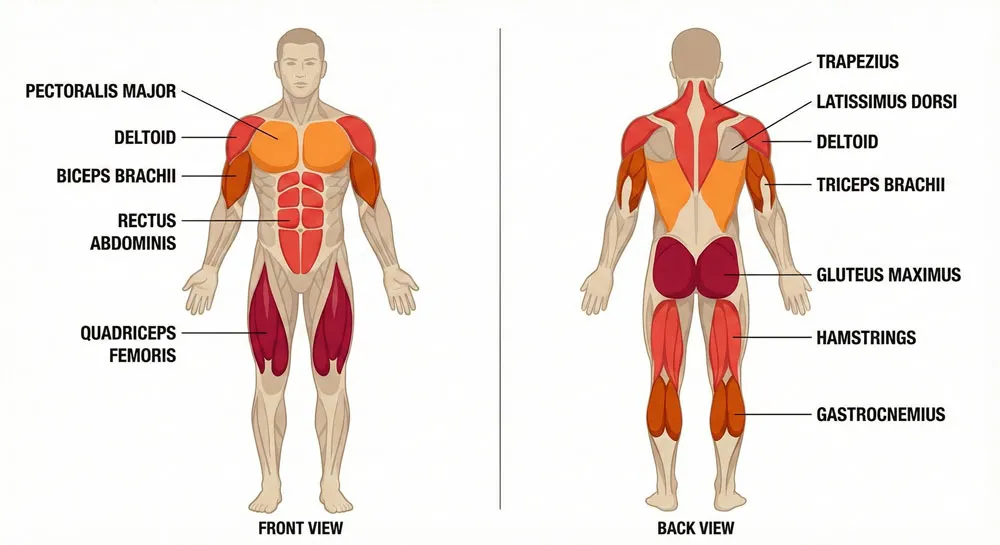

Layer 2: Muscles (Creating the Shape You See)

Muscles cover the skeleton and create the visible shapes you see on the surface. The good news: you don’t need to draw every individual muscle. You need to understand muscle groups and how they create visual shapes on the body.

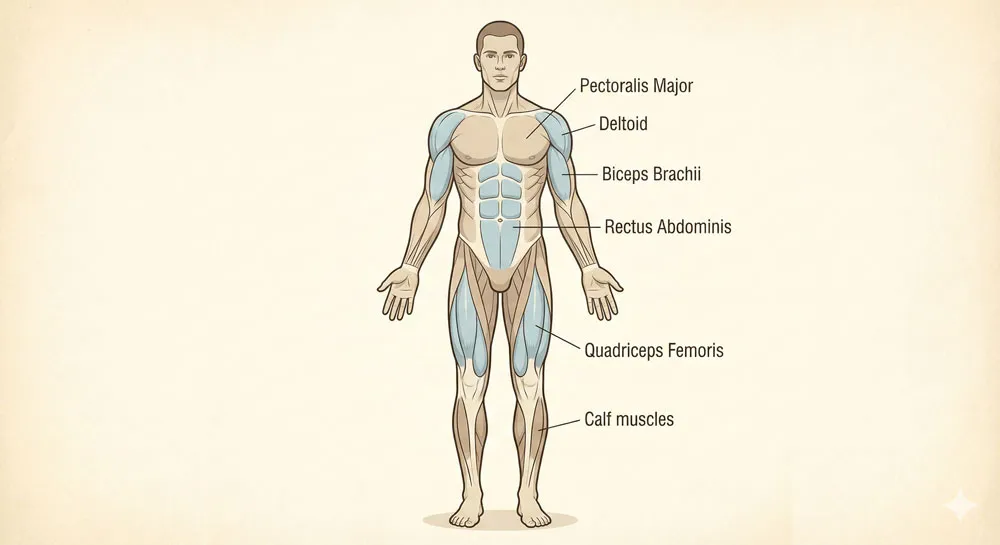

The muscle groups beginners need to understand:

- Shoulder muscles (deltoids) – Create the rounded shoulder shape

- Chest muscles (pectorals) – Define the upper chest width

- Abdominal muscles (abs) – Create visible segments on the torso (when visible)

- Back muscles (latissimus dorsi) – Create the V-shape of the back and determine arm position

- Leg muscles (quadriceps, hamstrings, calves) – Define the leg shape and movement

Here’s the beginner-friendly truth: you don’t need to draw anatomy like a medical student. You’re creating visual forms, not labeling muscles. When you understand how muscles group together, you can simplify them into shapes—which is exactly what professional artists do.

Related Topics:

Layer 3: Skin (The Final Form)

Skin is what you actually see. It wraps around everything underneath and creates subtle shapes and shadows based on the muscle and bone structure beneath it.

What beginners need to know about skin:

- It follows the shapes created by the skeleton and muscles

- Skin wrinkles, creases, and folds happen where the body bends or where muscles are flexed

- Skin color and texture vary but don’t change the underlying structure

- You don’t draw skin details first—you establish the form first, then add skin details like wrinkles and definition

Parts of the Human Body

| Parts | Description |

|---|---|

| Head | The uppermost part of the human body |

| Neck | Connects the head to the body or trunk |

| Shoulders | Connects the arms to the body or trunk |

| Hands | Symmetrical and both are placed on either side of the body |

| Chest | Part of the human body between the neck and the diaphragm |

| Abdomen | Region of the body between the thorax and the pelvis |

| Hips | Region on either side of the body that lie below the waist and above the thigh |

| Legs | The lowermost part of the human body |

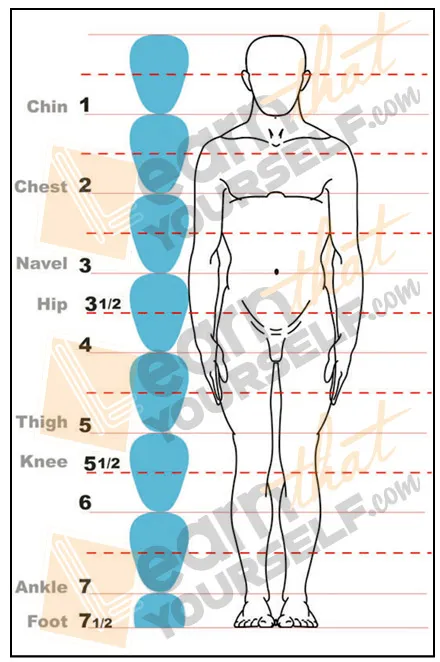

Human Body Proportions Explained Simply

This is where many beginners get confused. Let me break this down in the clearest way possible.

The Head as Your Measuring Unit

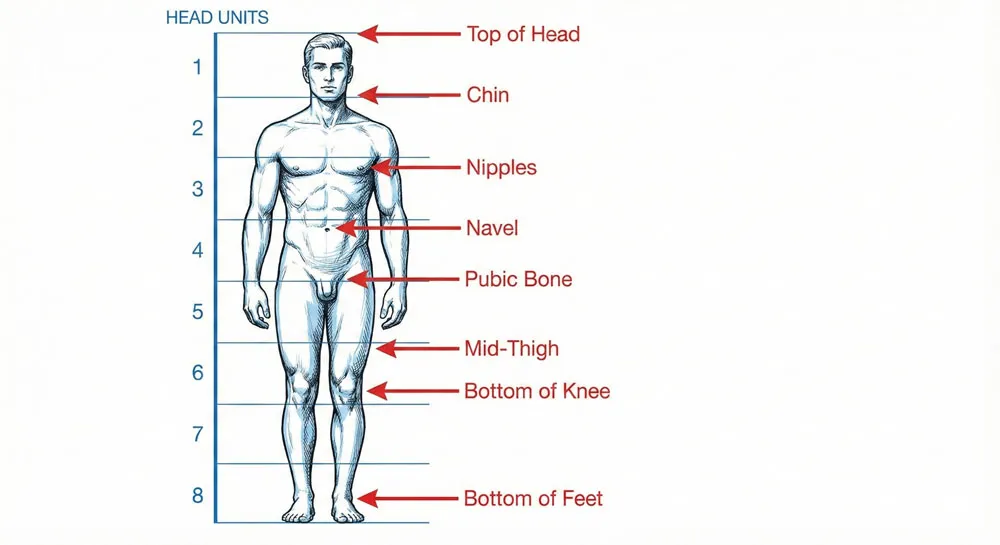

Every professional artist uses the same system: the head as a measuring unit. This is called “head units” or “heads tall.”

Here’s the simple version: An adult human body is roughly 7-8 times the height of their head.

This doesn’t mean you need to measure things obsessively. It means this:

- If you draw a head that’s 2 inches tall, your entire figure should be roughly 14-16 inches tall

- The proportions stay consistent no matter how large or small you draw

Breaking Down the Proportions (What Goes Where)

Instead of memorizing numbers, think about landmarks:

| Body Section | Position from Top | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Top of head to chin | 0-1 head | Defines head placement |

| Top of head to shoulders | 1-1.5 heads | Determines neck length |

| Shoulders to waist | 1.5-3.5 heads | Defines torso length |

| Waist to pelvis | 3.5-4.5 heads | Determines lower torso |

| Pelvis to knee | 4.5-6.5 heads | Upper leg proportions |

| Knee to ankle | 6.5-7.5 heads | Lower leg proportions |

Why this system works: Your body isn’t randomly proportioned. There’s a mathematical harmony that makes figures look “right.” When you understand these landmarks, you can place everything correctly.

Male vs. Female Proportions (Basic Differences)

Important note for beginners: The basic skeleton and proportions are the same between genders. The main differences are:

- Female figures: Wider pelvis, narrower shoulders, smaller rib cage, less visible muscle definition (typically)

- Male figures: Wider shoulders, narrower pelvis, larger rib cage, more prominent muscle shapes (typically)

These are generalizations—real bodies vary widely. But for learning, understanding these baseline differences helps.

Related Topics:

Step-by-Step Construction Method: How to Build a Figure from Scratch

This is where the magic happens. Instead of trying to draw a realistic human immediately, you’ll use a construction method—building your figure from basic shapes, step by step. This is what every professional animator and illustrator uses.

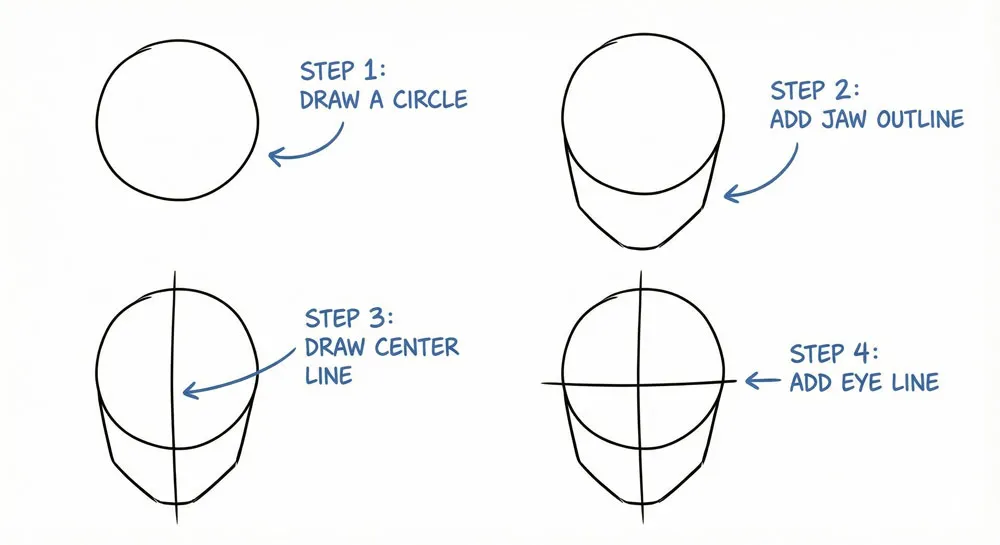

Step 1: Start with the Head and Spine Line

The very first thing you do is establish the head size and the spine line (the line of action).

- Draw a circle for the cranium (brain case)

- Below it, add the jaw shape (slightly smaller)

- Add a vertical center line through the head—this shows which direction the head is facing

- Add a horizontal line through the eyes—this is the eye level

- Draw a curved or straight line extending down from the bottom of the head—this is your spine line

Why this works: The spine line determines the entire pose and posture. If your spine line is straight, your figure is formal and rigid. If it’s curved, your figure has movement and personality.

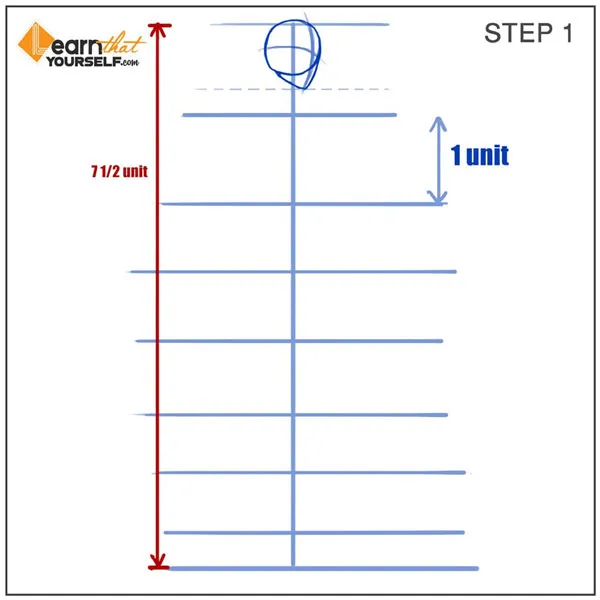

So, when you are going to draw a human figure, you’ll not be starting off with the details. You will be building the details bit by bit. The start will be from the skeleton (not a literal skeleton). Here, I mean skeleton breakdown or construction lines.

The reason we use construction lines in a drawing because if you start drawing with details then your drawing can very quickly get out of proportion as we haven’t established how things are going to look in a simple form.

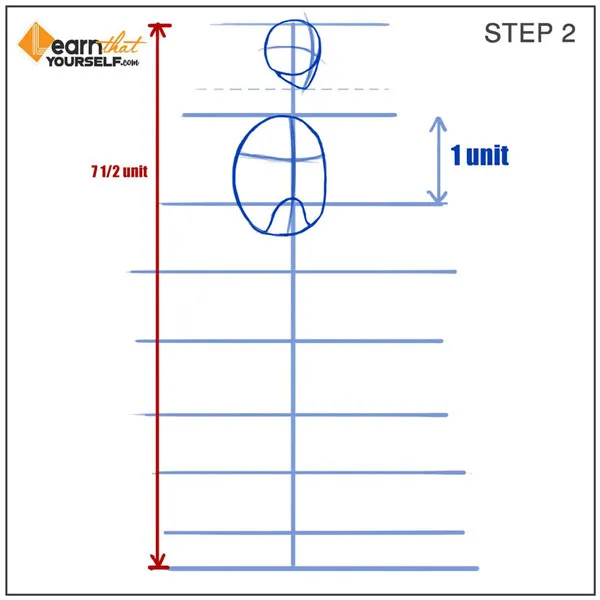

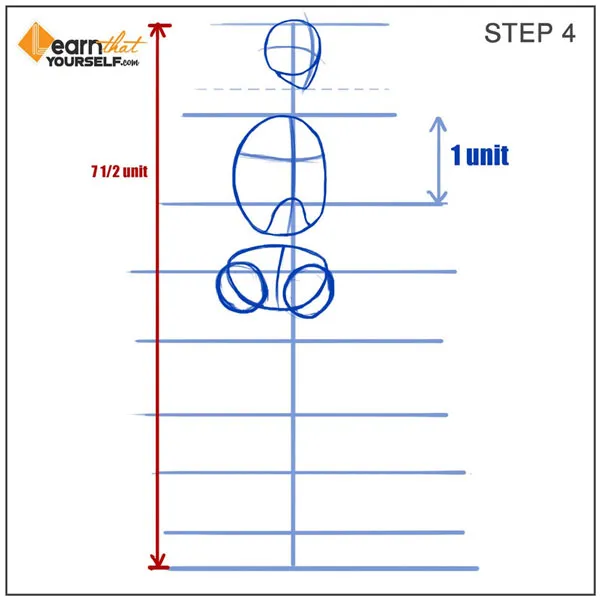

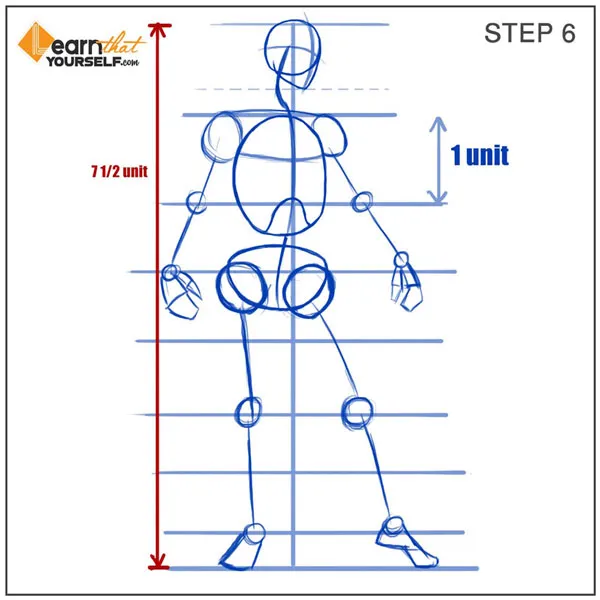

Therefore the first step would be to create the geometry of the skeleton in a simpler form as possible. A generic proportion to use for human anatomy is seven and a half heads in height and three heads in width.

- For the head part, I break it up into two parts. We have the cranium, which is just a circle and the second part is the jaw (the lower part). I’ve added two lines in the head part, a vertical and a horizontal. The vertical line will be indicating the direction that the head is facing and the horizontal line indicates the eye level.

Related Topics:

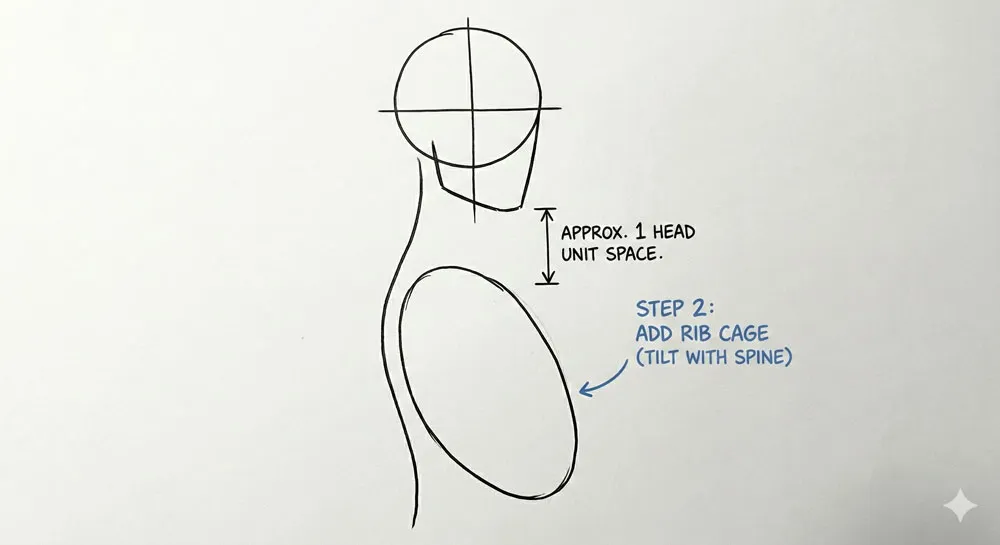

Step 2: Add the Rib Cage

Now you’re building the torso. The rib cage is the second largest mass on the body.

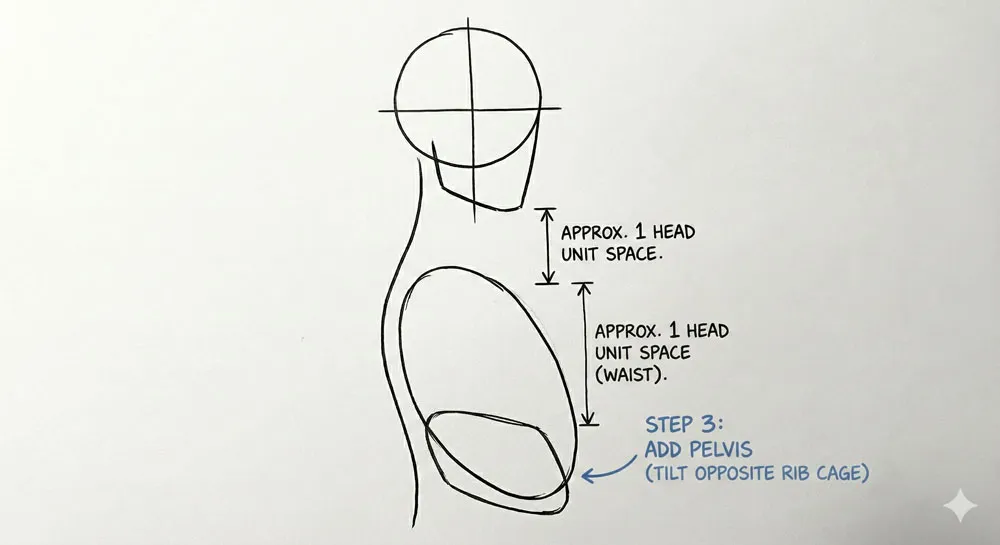

- Starting at roughly 1.5 heads below the chin, draw an oval or egg shape

- This oval should be tilted to match your spine line (if the spine curves, the rib cage follows)

- Add a convex line at the bottom of the rib cage to show the lower ribcage/sternum area

- Add a horizontal line through the middle to show the direction the rib cage is facing

Critical point for beginners: The rib cage is not the same as the belly. The rib cage is your torso bones. Many beginners make the rib cage too small, then add a massive belly, which ruins proportions.

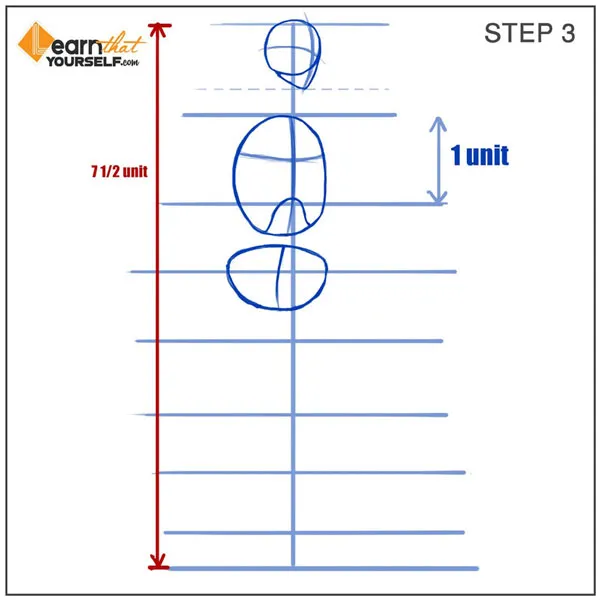

- Moving on to the next part, it is the rib cage. As you can see, I’ve started off with an oval shape and I added a convex shape in the lower part of the oval to just show the shape. Few indication lines for the direction and angle of the rib cage.

Step 3: Add the Pelvis

The pelvis is your third major mass.

- Starting about 2 heads below the rib cage, draw another oval

- This oval is usually slightly narrower than the rib cage for male figures

- Add direction lines through the pelvis to show if the hips are tilted or level

- Connect the rib cage and pelvis with a vertical line representing the center of the torso

Common beginner mistake: The pelvis is too small or positioned too close to the rib cage. When these two masses are too close together, your figure looks compressed and unrealistic.

- Next part is the pelvis. And here, I just went with another oval with two direction lines.

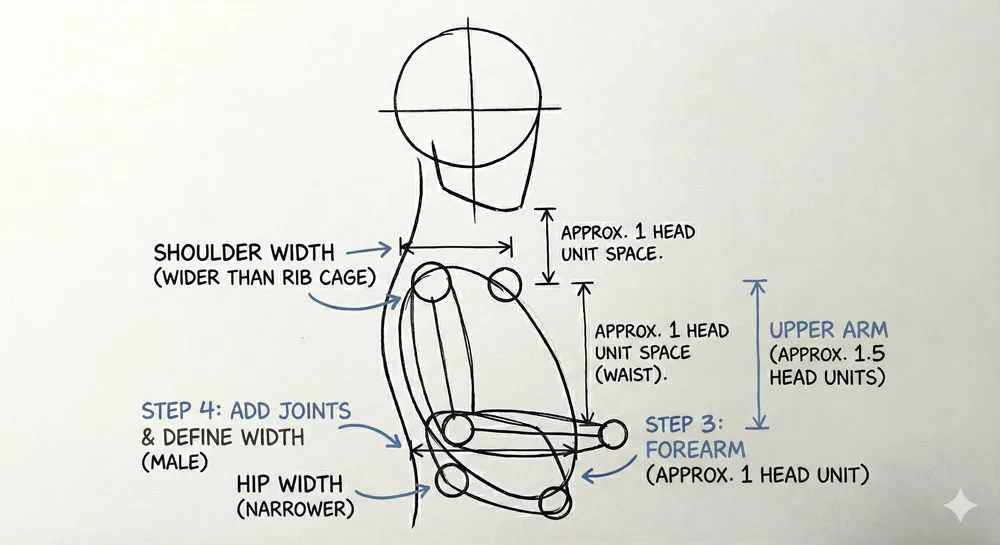

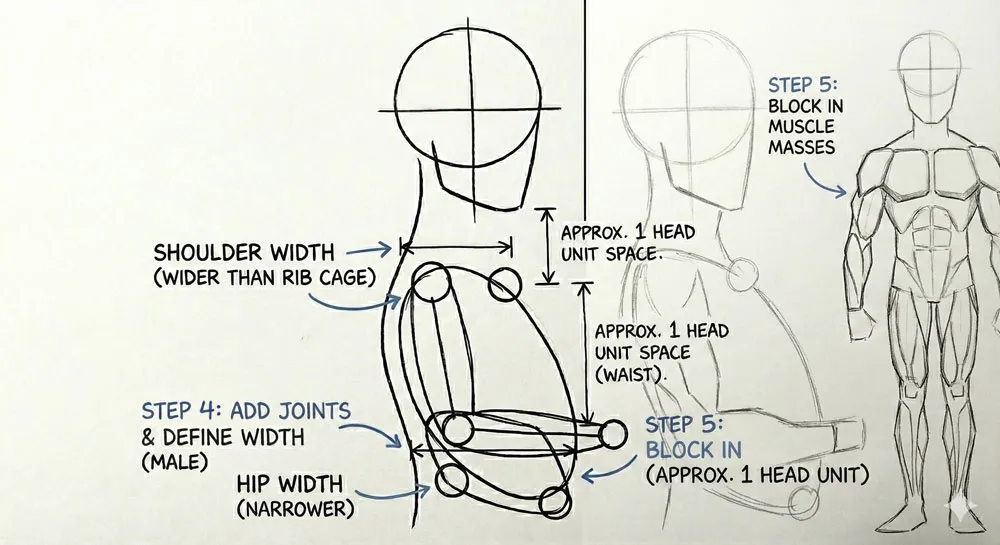

Step 4: Build the Shoulder and Hip Framework

Now you’re adding the joints where limbs attach.

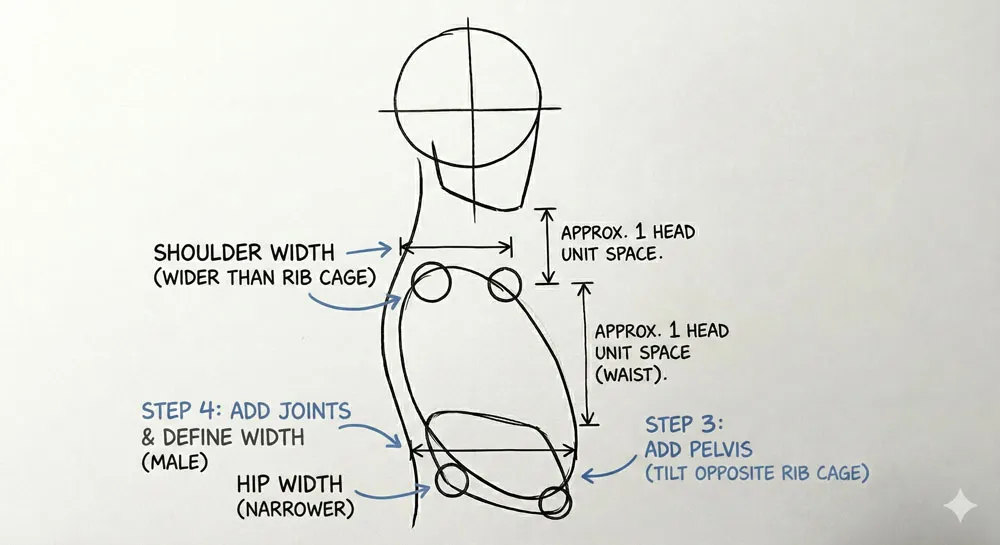

- For shoulders: Add two small circles on either side of the rib cage (at the top corners), about 1/2 to 1 head unit wide apart (wider than the rib cage itself)

- For hips: Add two small circles on either side of the pelvis, roughly aligned with the hip shape

- Connect shoulders to the spine with light lines

- Connect hips to the spine with light lines

Why circles work: Joint areas have bulk and mass. Using circles forces you to remember that shoulders aren’t just thin attachment points—they’re volumetric and important to the overall shape.

So, I tend to add circles for the shoulders because in the end there will be quite a large amount of mass there.

- I also worked with circles for where the hips start and turn into legs.

For the middle of the torso, I usually go with a line but some artists also go with another circle in the middle. But everybody has different kind of preferences. Everyone has a different method of going about the construction line.

There is no right or wrong way. It is the means to an end and you just want to use a reliable method for your medium as possible.

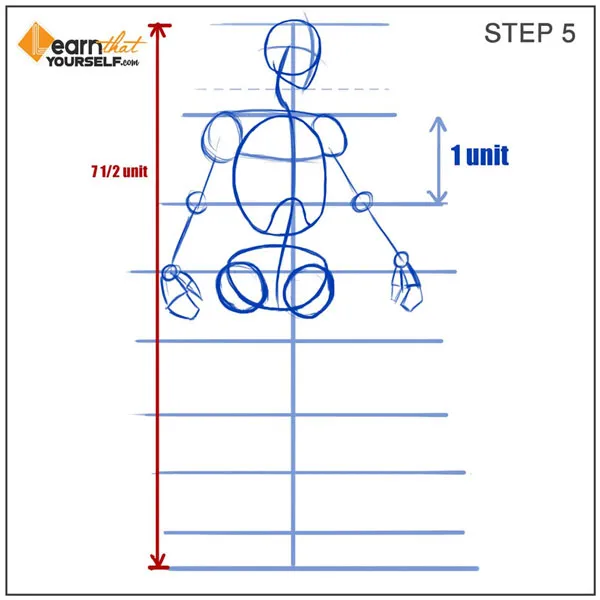

Step 5: Build the Limb Armature (Arms)

Arms are surprisingly simple once you break them down.

- From each shoulder circle, draw a line representing the upper arm bone

- At the elbow, make a small circle (the joint)

- From the elbow, draw a line to the wrist area

- Make a small circle at the wrist

- From the wrist, add a shape representing the hand

Critical point: Elbows don’t line up with the center of the body. They line up roughly with the waist. If your elbows are too high, your arms look too short. If they’re too low, they look too long.

- I then go for a line in the neck where the spine goes and then start adding lines for the limbs. For the elbow joint I make little circles and from there I let the arms out.

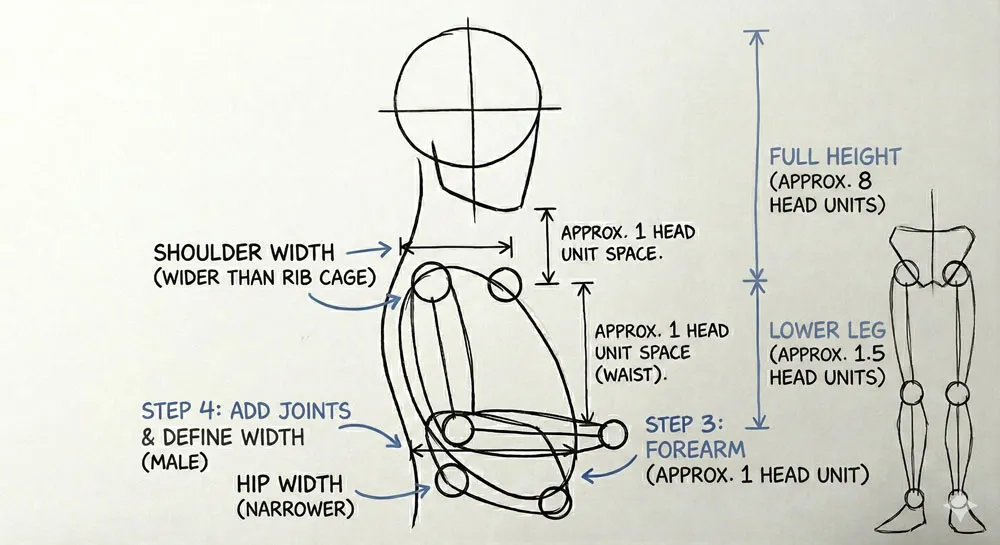

Step 6: Build the Limb Armature (Legs)

Legs are built the same way as arms: bone, joint, bone, joint.

- From each hip circle, draw a line down representing the thigh bone

- At the knee (roughly 2 heads down from the pelvis), make a small circle

- From the knee, draw a line to the ankle

- At the ankle, make a small circle

- From the ankle, add the foot shape (angled correctly for the pose)

Key proportion: The upper leg (thigh) and lower leg (shin) are roughly equal length. If one is much longer than the other, proportions are off.

- From the pelvis, I bring down the lines and made it up to the little joint in the knees and lastly, the lines down to where the legs end up going.

And that is my human skeleton. Even though it might look quite simple but from here we essentially add chunks and work with the shape to build the silhouette. So, bit by bit we are able to see our final result emerge.

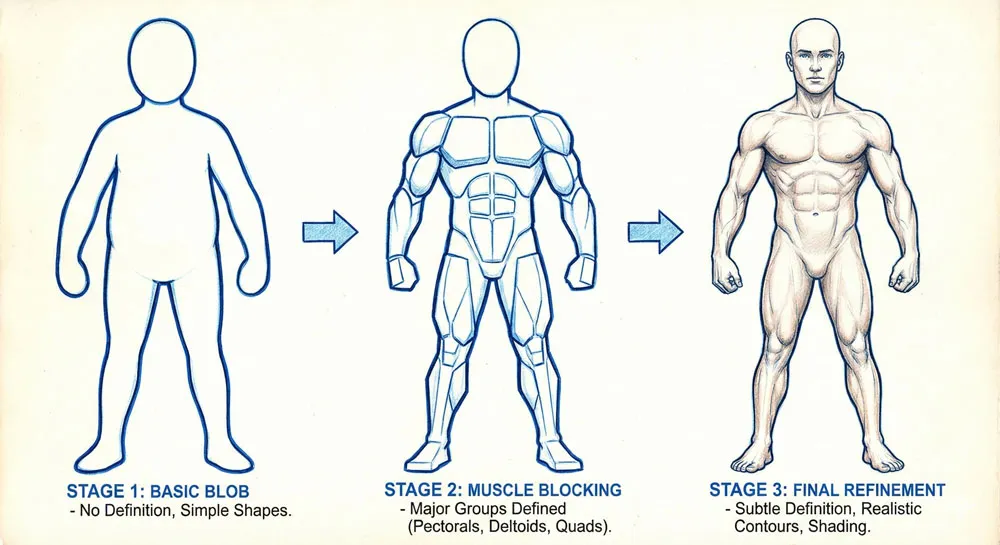

Step 7: Block in the Muscle Masses

Now comes the step where it starts looking like a human.

- Instead of circles and lines, you start roughing in the general shapes of muscle groups

- Don’t detail individual muscles—just block in the bulk of the shoulders, chest, biceps, thighs, calves, etc.

- Look for major shapes: Is the shoulder a cylinder? Is the thigh a tapered column?

- Refine the outline so you have a basic silhouette that looks human

This is the biggest jump for beginners: The construction lines transform into an actual figure. Don’t try to add details here—just establish the overall shape and volume.

- And in the next process, roughly block out where the muscles group will go. You don’t need to add the details yet.

So, as you can see up to this point we’ve drawn a rough sketch of a human figure starting off with only a few construction lines.

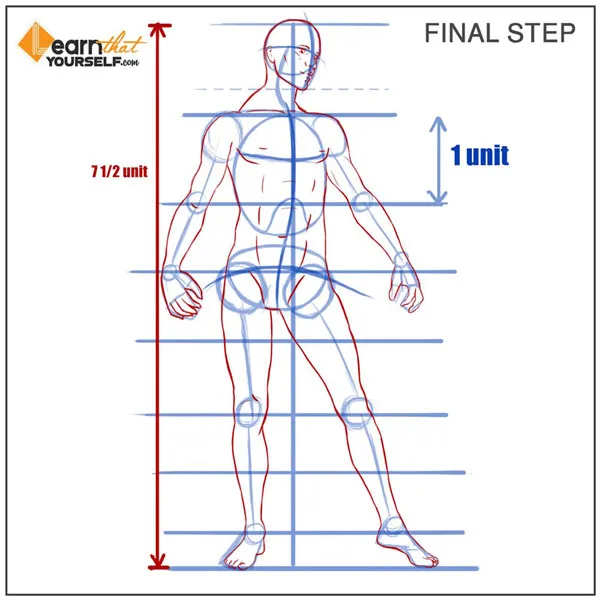

Drawing the Male Figure: Front View

Now that you understand the construction method, let’s apply it to a specific pose: the male figure facing forward.

As the figure clearly shows, the general proportions of a male human body (front post or front angle). The proportion of the male human body is measured from the top of the drawing using the ‘Head’ as the standard unit of measurement.

Front View Proportions (Quick Reference)

For a standing male figure viewed from the front:

- Head to shoulders: 1-1.5 head units

- Shoulder width: Approximately 2.5-3 head units wide (widest point of the upper body)

- Rib cage width: Approximately 2 head units

- Waist to pelvis: Approximately 1 head unit

- Hip width: Approximately 2-2.5 head units (slightly narrower than shoulders)

- Full body height: 7.5-8 heads

What Makes the Front View Unique

In the front view:

- Symmetry is key – Both sides should mirror each other (unless the pose has asymmetry)

- The centerline matters – A vertical line through the center helps you keep proportions balanced

- Muscle definition is visible – Chest, abs, and frontal leg muscles are visible from this angle

- The ribcage width is important – In front view, the rib cage creates the visual width of the upper body

Construction for Front View

Follow the same construction method as above:

- Head and spine line (keep spine straight for neutral posture)

- Rib cage (keep it symmetrical)

- Pelvis (aligned with rib cage centerline)

- Shoulders and hips (equal and balanced)

- Arms (both sides mirrored)

- Legs (both sides mirrored)

- Muscle blocking

- Refine and add details

The key difference in front view: absolute symmetry until you add dynamic poses.

Related Topics:

Drawing the Male Figure: Side View (Profile)

The side view reveals different proportions and makes certain anatomical features obvious.

Side View Proportions (Quick Reference)

From the side (profile), the proportions shift slightly:

- Head to chin to neck: 1 head unit (same as front)

- Neck to shoulder tip: Approximately 0.5 head units

- Shoulder depth (front of chest to back): Approximately 1.5-2 head units

- Upper body tilt: In a natural stance, the entire upper body leans slightly forward

- Foot length: Approximately 1-1.5 head units

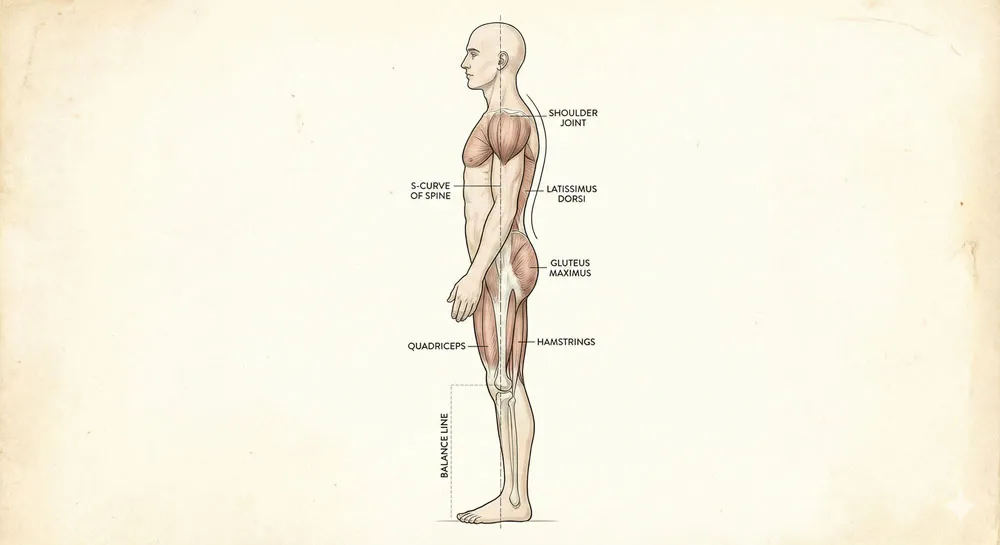

- The curve of the back: Never completely straight—has a natural S-curve

What Makes the Side View Unique

In profile:

- Depth becomes visible – You see chest depth, rib cage depth, and pelvis depth

- The spine curve is obvious – The natural S-curve of the human spine is visible (cervical, thoracic, lumbar curves)

- Muscle groups show differently – The shoulder appears as a single mass from the side; the back muscles create the body’s outline

- Balance point matters – The figure’s balance shifts based on where the legs position under the body

Key Anatomical Points in Side View

- The ear aligns roughly with the shoulder – In a neutral standing position

- The rib cage projects forward – It’s in front of the pelvis slightly

- The knee bends slightly – Even in standing poses, the leg isn’t locked straight

- The foot connects at an angle – The sole isn’t a flat line; it shows ankle structure

Construction for Side View

Use the same construction method, but pay attention to:

- Depth of each mass – The rib cage, pelvis, and head all have depth from the side

- The spine curve – Your spine line won’t be perfectly straight; it has the natural S-curve

- Joint alignment – The knee should align under the hip, not in front or behind

- Foot placement – The foot should position so weight is balanced

Related Topics:

Drawing the Male Figure: Back View

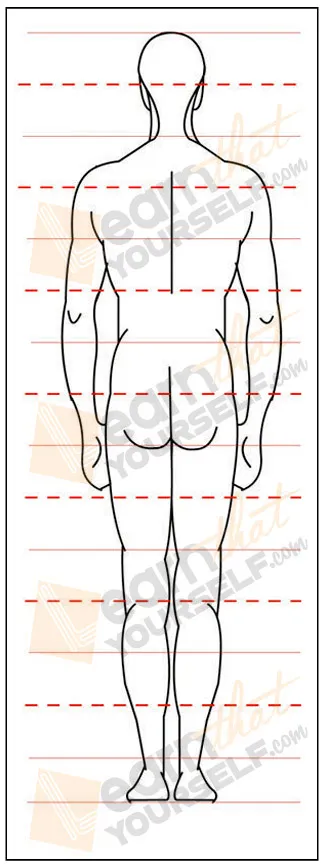

The front view and back view of a male human body are very similar which can easily be seen in the figure.

- The lower edges of the shoulder blades are two head units down from the head.

- The shoulders are a little over two head units.

- The hips are about one and half head units.

- The lower edges of the buttocks fall a little below the midpoint of the male human body.

- The horizontal creases at the back of the knee that separates the upper and lower legs are a little above than two head units up from the heel.

The back view is often overlooked by beginners, but it’s essential for understanding the complete figure.

Back View Proportions (Quick Reference)

From behind:

- Shoulder blade placement: The lower edges of the shoulder blades are approximately 2 head units down from the top of the head

- Shoulder width: Approximately 2.5-3 head units (same as front view)

- Waist definition: More obvious from behind due to muscle anatomy

- Hip width: Approximately 2-2.5 head units (slightly narrower than shoulders)

- Buttocks position: Falls roughly at the 4-5 head unit mark, positioned between the hip line and knee

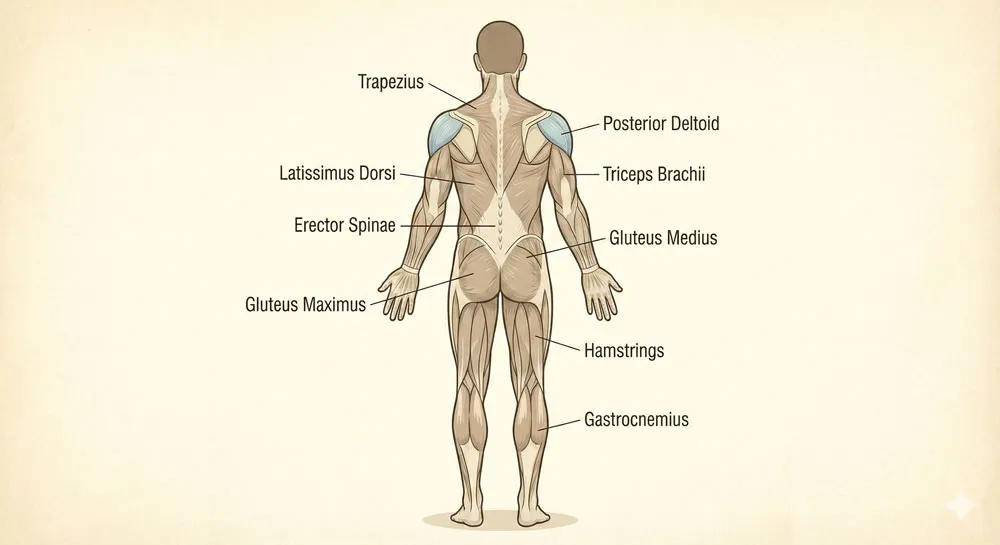

- Back musculature: Creates visible muscle shapes (trapezius, rhomboids, latissimus dorsi, erector spinae)

What Makes the Back View Unique

From behind:

- The back muscles create the body’s outline – The latissimus dorsi (back muscles) create the V-shape of the back or trapezius width

- The shoulder blades are visible – They influence the shoulder width and shape

- Leg definition is different – From behind, hamstrings and calves are prominent

- The spine line is subtle – You see the vertebrae line running down the center only in very lean figures

Key Anatomical Points in Back View

- The shoulder blades don’t stick out – They’re integrated into the shoulder mass

- The back is narrower at the waist – Creating the waist curve

- The buttocks are a distinct mass – They’re significant volume that many beginners miss

- The hamstrings are prominent – The back of the thigh is often more visible than the front

Construction for Back View

Use the same construction method:

- Head and spine (keep spine visible as a subtle centerline)

- Rib cage (wider at the top, narrower at the waist)

- Pelvis (positioned below the rib cage with proper spacing)

- Shoulders and hips (symmetrical)

- Arms (both sides mirrored, showing back of the arms)

- Legs (both sides mirrored, with hamstring/calf prominence)

- Block in back muscle masses

- Refine and detail

Related Topics:

Common Beginner Mistakes & How to Fix Them

Let’s address the errors that plague almost every beginner. Knowing what to avoid is just as important as knowing what to do.

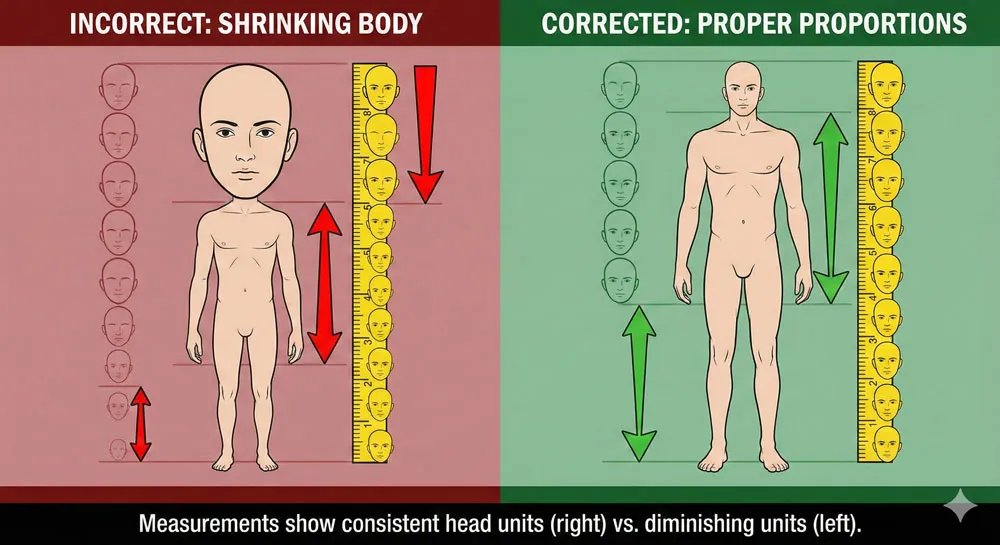

Mistake 1: Head Too Small or Body Shrinking as You Go Down

The problem: Beginners often draw a normal-sized head, then make the shoulders smaller, the hips even smaller, and the legs tiny. The result: an upside-down ice cream cone.

Why it happens: You lose confidence as you draw downward. The head feels “right,” but then you’re not sure about size, so you make safer, smaller choices.

The fix:

- Draw your 7-8 head tall reference line from the beginning

- Commit to the proportions: shoulders should be wider than the head, not narrower

- Check proportions halfway through: measure if the pelvis width looks right relative to shoulders

- Remember: hips are usually slightly narrower than shoulders (especially on males), not dramatically smaller

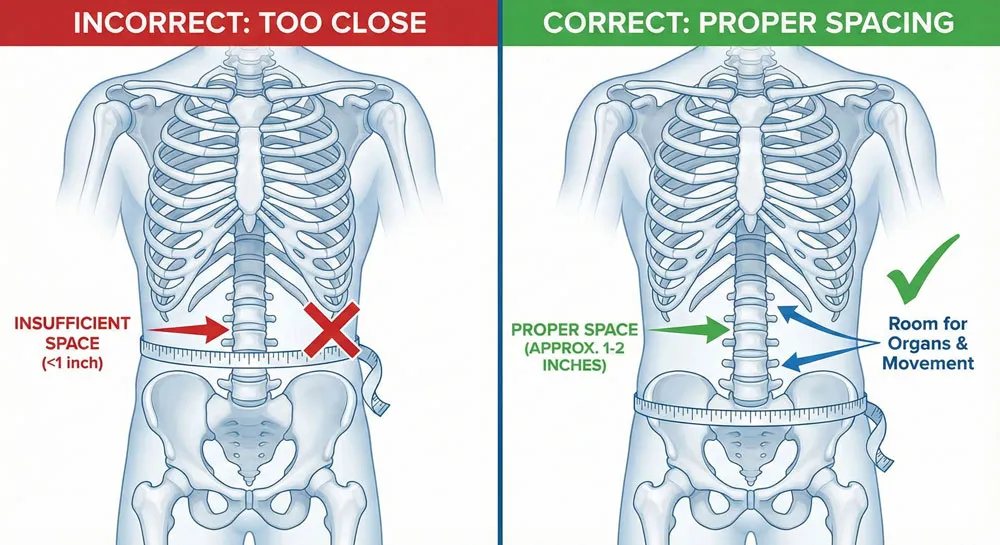

Mistake 2: Rib Cage Positioned Too Low or Too Close to the Pelvis

The problem: The torso looks compressed and unrealistic. The figure looks like it has no waist or midsection.

Why it happens: Beginners aren’t sure of the rib cage size, so they underestimate it. They rush and don’t give proper space between rib cage and pelvis.

The fix:

- The rib cage should be approximately 2 head units tall

- There should be clear space (about 1 head unit) between the bottom of the rib cage and the pelvis

- Draw the rib cage to touch your construction line—don’t make it smaller to be “safe”

- Use your proportion references: the rib cage extends from about 1.5 heads to 3.5 heads (roughly)

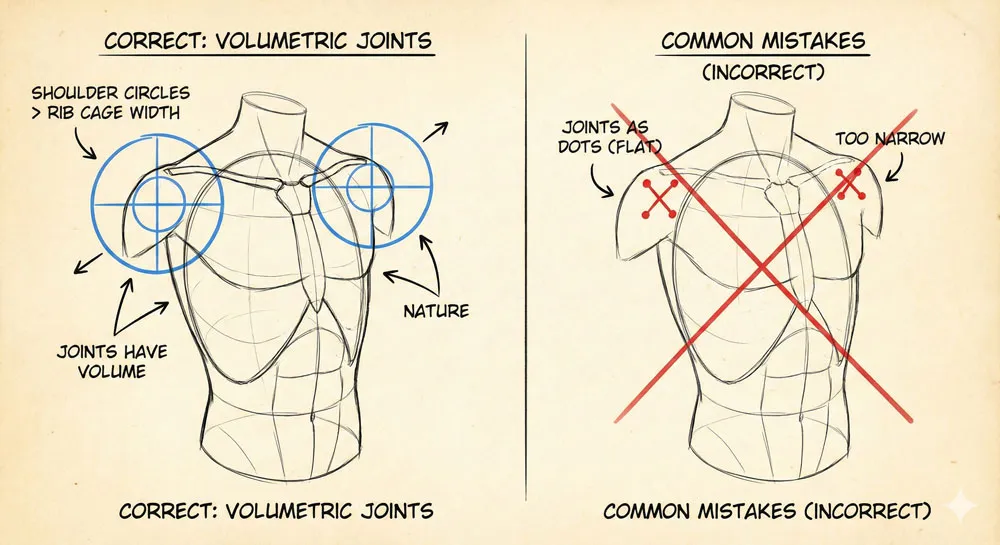

Mistake 3: Shoulders Too Narrow or Joints Not Circular

The problem: The shoulders look wimpy and the joints (shoulders, knees, elbows) look flat instead of three-dimensional.

Why it happens: Beginners are afraid of drawing something “wrong,” so they make cautious, small shapes. Also, joints aren’t always obvious in real life, so beginners don’t think they’re important.

The fix:

- Draw shoulder circles that are clearly 2-3 head units wide

- Remember: shoulders sit outside the rib cage edges

- Make joints with actual circles (or ovals in perspective)—not tiny dots

- Joints have volume; they’re where bones connect and muscles group, so they’re bulky

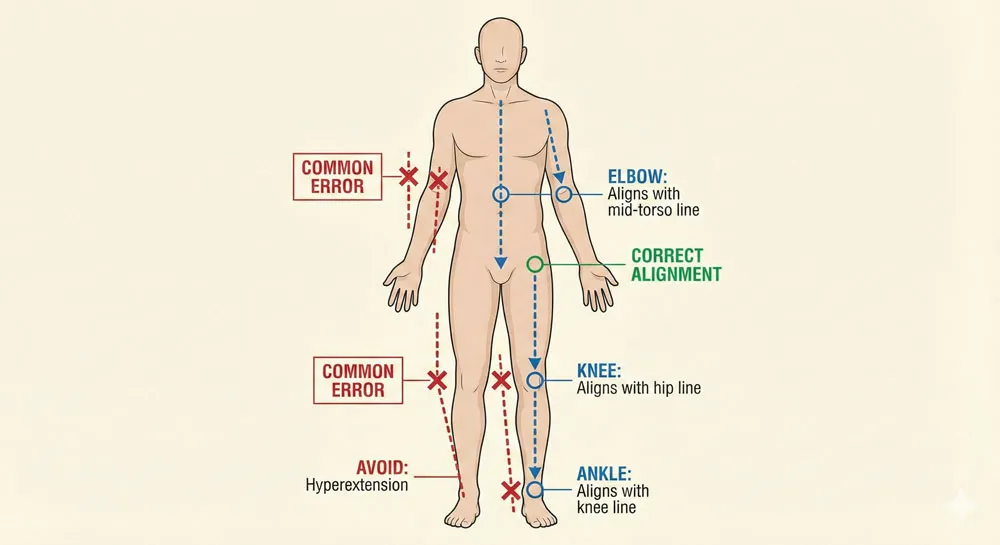

Mistake 4: Arms and Legs Attached at Wrong Angles or Positions

The problem: Limbs look dislocated or the figure looks like it’s in an impossible position (even though it’s supposed to be standing neutrally).

Why it happens: Beginners don’t understand where joints actually attach. An elbow that’s too high makes the arm too short. A knee that’s too far forward makes the figure look like it’s falling.

The fix:

- Elbows: Should align with the waist (about the 3.5-4 head mark from the top)

- Knees: Should align under the hip joint (roughly the 6-6.5 head mark)

- Shoulder sockets: Should be part of the rib cage (not floating above it)

- Hip sockets: Should be integrated into the pelvis (not floating below)

- Use vertical alignment: drop a line from the hip to check if the knee is beneath it

Mistake 5: No Muscle Definition or Overly Detailed Anatomy

The problem: Either your figure looks like a featureless blob, or you’ve added so much anatomical detail that it’s confusing and looks stiff.

Why it happens: Beginners either don’t know where muscles go, or they know just enough to over-complicate things.

The fix:

- Start simple: Before adding any muscle, your figure should have a clear silhouette and proper proportions

- Add muscle groups, not individual muscles: Block in the shoulder, chest, arm, quad, calf—don’t detail every small muscle

- Use subtle lines: Muscle definition comes from light lines showing borders and shadow areas, not heavy outlines

- Save details for last: Only add muscle detail after form and proportions are 100% correct

Practice Challenges to Master Anatomy

Knowing anatomy and being able to draw it are different skills. Here are targeted exercises to develop muscle memory and intuition.

Challenge 1: The Proportion Grid

What to do:

- Draw a rectangle 8 head units tall and 3 head units wide

- Draw 8 horizontal lines dividing the rectangle into equal sections (each 1 head unit apart)

- Without looking at references, construct a male figure and mark where each major landmark should fall

- Then check against your reference: are your landmarks where they should be?

Why it works: This trains your eye to understand proportions without thinking about it.

Repeat: 10-15 times until you can place landmarks correctly without referencing

Related Topics:

Challenge 2: Construction Skeleton Speed Drill

What to do:

- Set a timer for 2 minutes

- Draw a complete construction skeleton (head, spine, rib cage, pelvis, shoulders, hips, limbs) as accurately as possible

- After the timer, check proportions: is everything the right size relative to the head unit?

- Repeat with different poses (standing, sitting, leaning)

Why it works: Speed forces you to trust your understanding instead of second-guessing yourself. Also trains muscle memory.

Repeat: 20-30 complete skeletons across multiple sessions

Challenge 3: Mirror Pose Challenge

What to do:

- Draw a figure from the front view, then immediately draw the exact same figure from behind (no looking at your front view drawing)

- The back view should match the front view in proportions and pose

- This trains you to understand the full 3D figure, not just what’s visible from one angle

Why it works: Most beginners can only draw from their dominant angle. This trains complete spatial understanding.

Repeat: 10-15 pairs of figures

Challenge 4: The No-Reference 10-Figure Challenge

What to do:

- Without any references, draw 10 complete figures in different poses (front, side, back, sitting, kneeling, etc.)

- No looking at photos or references—only your knowledge

- After drawing all 10, compare them to anatomy references and mark where proportions are off

- Repeat the challenge in one week and see if you’ve improved

Why it works: This tests your actual understanding vs. your ability to copy references. The errors you find are your real learning priorities.

FAQ: Your Anatomy Drawing Questions Answered

Q1: Do I need to memorize every muscle name to draw anatomy?

No. You don’t need to know that the “rectus femoris” is the front thigh muscle. You need to know that the front of the thigh has a muscle group that creates a specific visible shape. Think in terms of shapes and visual landmarks, not Latin names. Medical students memorize names; artists memorize visual forms.

Q2: Why do my proportions look wrong even when I’m measuring?

Most likely cause: You’re measuring individual parts correctly but not considering the overall relationship. Check:

- Is your head the right size relative to the whole body?

- Are your shoulders wide enough relative to your head?

- Is there enough space between rib cage and pelvis?

Fix: Always start with the whole and work to the parts, not the reverse.

Q3: How long does it take to get good at anatomy drawing?

It depends on practice volume, not calendar time. Drawing 15 anatomically-conscious figures per day will improve you faster than drawing casually once a week. Most artists see significant improvement within 30-50 complete figure drawings with focused attention on anatomy. Expect 3-6 months of consistent practice to feel comfortable.

Q4: Should I draw from photographs or from imagination first?

Start with references, build to imagination. Draw 10-15 figures from references while understanding anatomy. Then attempt 5-10 from imagination. You’ll see where your knowledge gaps are. Fill those gaps by drawing references again. This cycle of reference → imagination → identification of gaps → more references is how you develop real understanding.

Q5: What’s the difference between “stylized” and “anatomically correct”?

Anatomically correct means structurally accurate—bones, joints, proportions follow real anatomy. Stylized means you intentionally exaggerate or change anatomy for artistic effect (shorter legs, larger head, etc.). You need to understand anatomically correct anatomy first. Then you can stylize it knowingly instead of accidentally creating broken proportions.

Q6: Why do my figures look stiff even when proportions are correct?

Likely causes:

- You’re using completely vertical spine lines; add subtle curves for life

- Your joints look flat (circles not actual 3D forms); make them bulky

- Your limbs are parallel instead of at varied angles

- You’re not adding any weight shift or stance to indicate balance

Fix: After proportions are correct, focus on gesture and flow. Add energy to your poses.

Q7: Is it better to draw digitally or on paper for learning anatomy?

For learning, either is fine. Some people prefer paper for the tactile feedback. Some prefer digital for the ability to easily erase and adjust. The medium doesn’t matter; the practice does. Choose whichever you’ll actually use consistently.

Q8: How do I draw anatomy in different styles (manga, cartoon, realistic)?

Master realistic anatomy first. Once you understand the real structure, you can exaggerate or simplify it knowingly. A cartoon style with broken anatomy looks like you don’t know anatomy. A cartoon style built on correct anatomy looks like intentional stylization.

Your Next Steps: From Knowledge to Skill

You now have the knowledge. The remaining step is simple: draw.

Start with the practice challenges outlined above. Spend 2-3 weeks doing construction skeleton drills and proportion studies. Then begin applying this knowledge to full figures. Keep anatomy references nearby—not to copy, but to verify your understanding.

The human body is beautiful to draw once you understand how it works. You’ve got the foundation. Now it’s time to build your skill through deliberate practice.

About the Author

Lalit M. S. Adhikari is a Digital Nomad and Educator since 2009 in design education, graphic design and animation. He’s taught 500+ students and created 200+ educational articles on design topics. His teaching approach emphasizes clarity, practical application and helping learners.

Learn more about Lalit Adhikari.

This guide is regularly updated with the latest information about Adobe tools and design best practices. Last Updated: Feb 2026

Related Topics:

Excellent blog you’ve got here on Human Anatomy for art. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours nowadays. I truly appreciate people like you! Take care!!

Definitely, what a splendid website and illuminating posts, I will bookmark your blog. Best Regards! Sukriya sir ji!

Spot on with this write-up on How to Draw human anatomy, I truly think this website needs far more consideration. I’ll most likely be coming back once more to read far more, thanks for that info.

Fantastic information from you, man. I have understood so many topics earlier too and you’re just too excellent. I can not wait to read far more from you. This is actually a wonderful web site.

Thanks for the good and informative writeup.

Excellent web site. Plenty of useful information here. I am sending it to several buddies and also sharing in delicious. And obviously, thank you in your effort!

Thanks for giving this info on this website.

The info, design and style of this blog is great! Many thanks!

Thanks for expressing your ideas.

Many thanks for sharing these types of wonderful articles. Thanks a lot!

Thanks for posting such a amazing article

Easy to understand and follow. Thanks alot!

Thank you for this wonderful article.