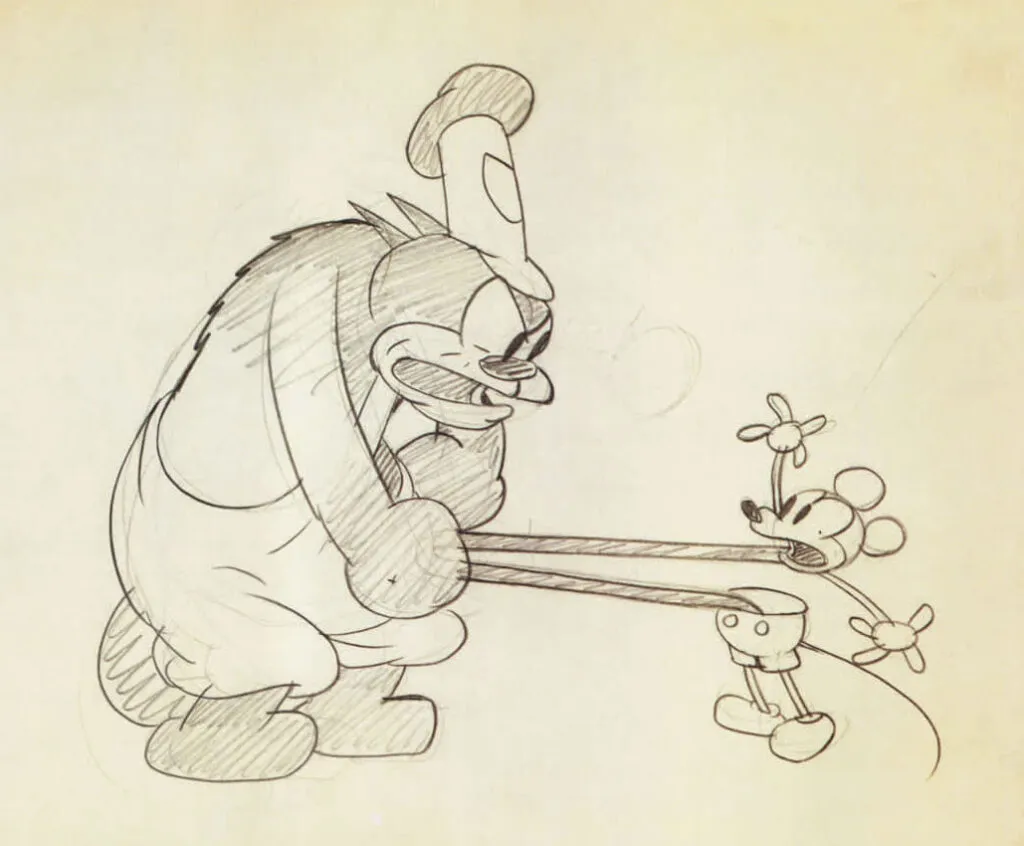

Ever wonder how Disney’s iconic characters like Mickey Mouse, Alladin, Woody & Buzz, Lightning McQueen & the others came to life on the page? It wasn’t spells or secret formulas—it was simple shapes.

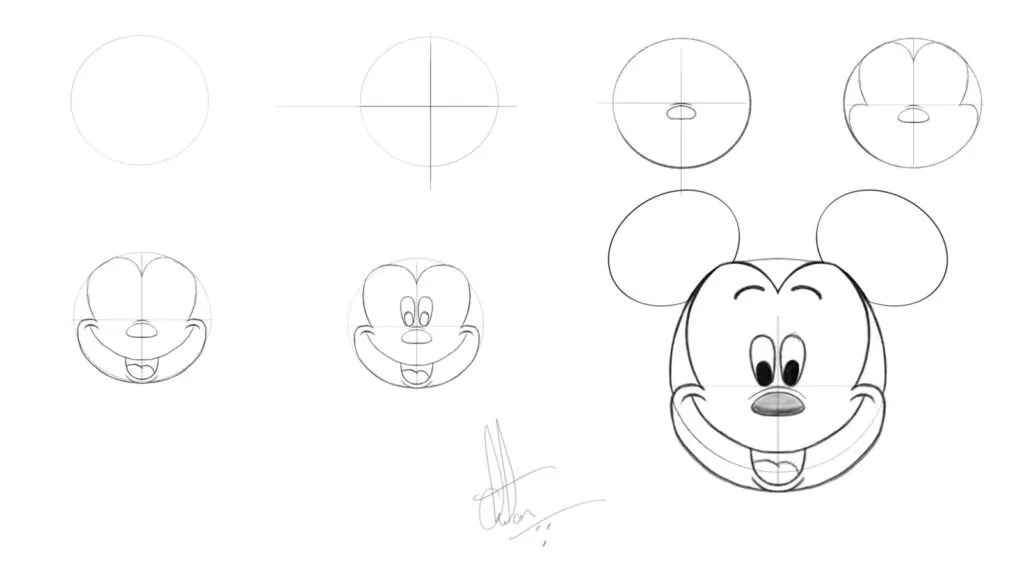

I was fifteen, when I first discovered the secret behind every Disney character, I’d ever loved. Sitting in my bedroom with a worn-out animation book borrowed from the library, I stared at a page showing Mickey Mouse’s construction.

There it was—plain as day—three circles. That’s all Mickey was. Three circles, some careful curves, and suddenly you had the most iconic character in animation history.

My mind exploded. All those years struggling to copy characters from memory and the answer had been hiding in plain sight: shapes. Just simple, basic shapes.

That revelation changed everything about how I approached drawing. Before that moment, I’d been intimidated by the polished, perfect characters I saw on screen.

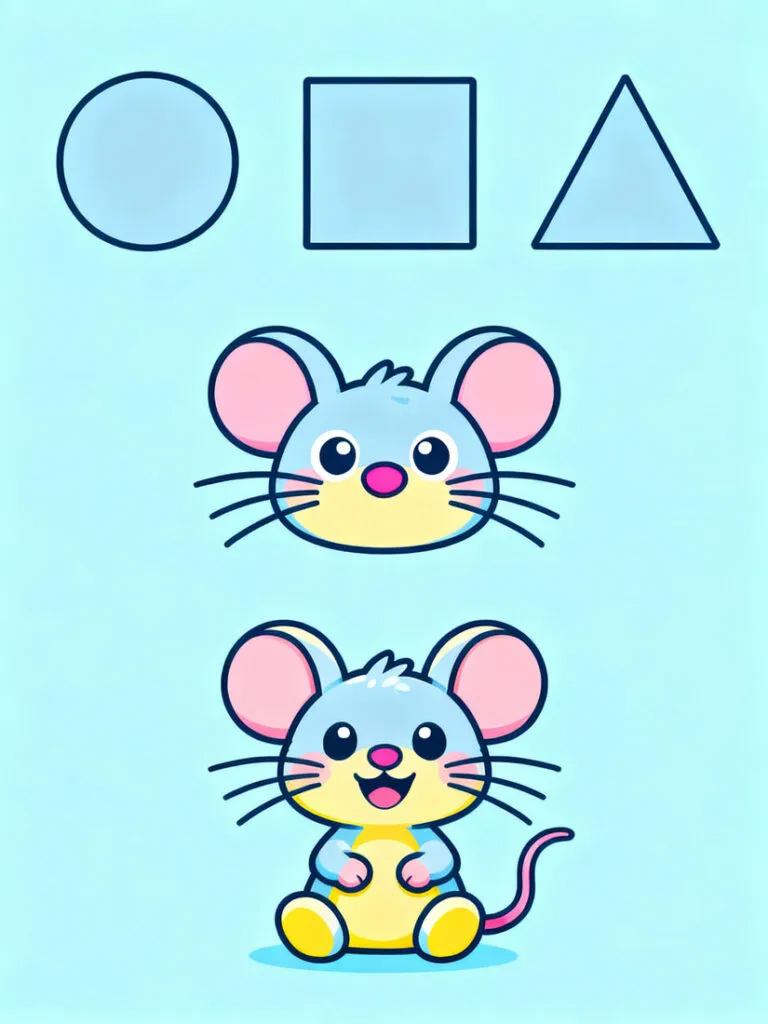

After? I realized that every legendary character, from Dumbo to Elsa, started exactly where I was—with someone’s pencil, a blank page and a handful of circles, squares and triangles.

The magic wasn’t in some mysterious artistic talent I didn’t possess. It was in understanding how to see the world through geometric eyes.

Over the years, as I transitioned from a struggling teenage artist to teaching animation students at Arena Animation, I’ve watched this same revelation hit dozens of students.

That moment when their eyes light up, when they realize they’ve been overcomplicating everything, when they draw their first Mickey using just circles and suddenly it actually looks like Mickey—that’s pure magic. And that’s what I want to share with you today.

Whether you’ve never picked up a pencil or you’re just starting to doodle, this guide will show you, how to build your favourite Disney (and Pixar!) heroes using nothing more than circles, ovals, rectangles, and triangles.

By breaking each character down into its most basic form, you’ll learn the exact “blueprint” that professional animators and artists use every day.

Table of Contents

Why Basic Shapes?

Every semester, I start my first class the same way. I ask students to draw their favorite Disney character from memory. Without fail, the room fills with nervous laughter and the sound of pencils scratching tentatively across paper.

What emerges are wonky, disproportionate characters that barely resemble their inspirations. Ears floating in wrong places. Bodies that don’t quite connect to heads. Eyes that seem to exist in different time zones.

Then I teach them the shape secret.

Simplicity Breeds Confidence

Starting with circles and rectangles keeps you from feeling overwhelmed. If you can draw a circle, you can start any character.

Last year, I had a student named Priya who was convinced she couldn’t draw. She’d sit in the back, arms crossed, insisting that some people were just “born artists” and she wasn’t one of them.

On day three, I gave the class their first shape exercise: draw Mickey Mouse using only circles. No references, no tracing—just circles. Priya rolled her eyes but picked up her pencil.

Fifteen minutes later, she was staring at her paper with her mouth open. There, on her sketchbook, was a recognizable Mickey Mouse. Not perfect, not portfolio-ready, but unmistakably him. “I did that,” she whispered. “I actually did that.”

By the end of the semester, Priya was designing her own characters and helping other students understand proportions. The shape secret had unlocked something she’d convinced herself didn’t exist.

Related Topics:

- The Ultimate Toolkit Guide for Artists

- What is Sketching? A Beginner’s Guide to the Art of Drawing

- 7 Fears All Successful People Must Overcome

Why every legendary character started as a circle

Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks weren’t thinking about creating an empire when they sketched the first iterations of Mickey. They were thinking about what shapes worked.

Circles were soft, approachable, friendly. They rolled and bounced naturally, which was perfect for animation. A circular head meant smooth rotation. Circular ears meant instant recognition from any angle.

This wasn’t accidental. Early animators had to draw the same characters hundreds of times per scene. Complex designs meant complex repetition, which meant mistakes and exhaustion.

Simple shapes meant consistency. A circle is a circle whether you’re drawing it at 2 PM on Tuesday or midnight on Friday. This practical necessity became the foundation of character design theory.

Structure & Proportion

Shapes act as a skeleton—placing them correctly ensures your character’s head, body and limbs all “talk” to each other in the right scale.

Flexibility

Once your shapes are down, you can tweak and refine. Want Woody’s hat to tip at a jaunty angle? Just rotate that oval!

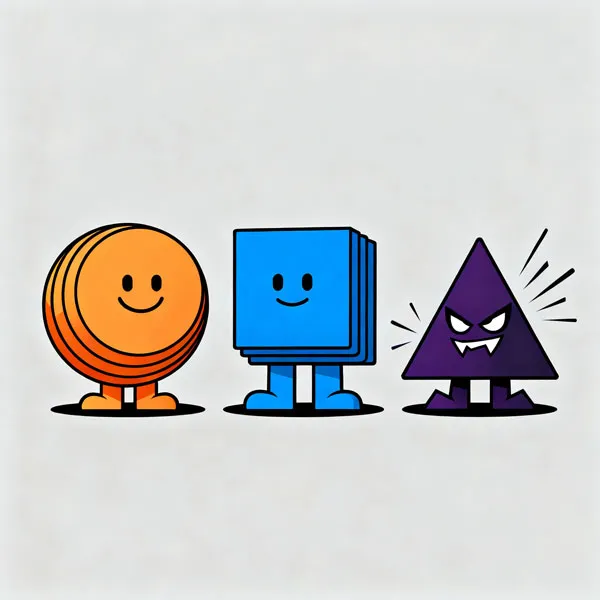

The psychology of shape recognition

Our brains are wired to recognize patterns, and geometric shapes are the most fundamental patterns we know. Before babies can identify faces, they respond to circles and contrasts. This deep, neurological preference for simple forms means that characters built from basic shapes feel inherently right to us. They tap into something primal and comforting.

Circles read as friendly, soft, and approachable. Squares suggest stability, strength, and reliability. Triangles imply danger, speed, and energy. When you understand this shape language, you’re not just drawing—you’re communicating on a subconscious level with your audience. Every curve and angle tells a story before you add a single facial expression.

Related Topics:

Your Starter Toolkit

You don’t need fancy supplies. Grab:

- Pencil (HB or 2B)

- Eraser (kneaded erasers are magic for lightening lines)

- Drawing Paper (newsprint or sketchbook)

- Sharpener

- Ruler or Straight-Edge (optional, for robot-like body parts)

Keep an open mind—this is about building confidence, not perfection. For more information on Sketch Tools, you can read my blog on The Ultimate Toolkit Guide for Artists.

Related Topics:

The Sketching Mindset

The blank page is a liar. It sits there, pristine and white, whispering that you’re about to ruin it with your inadequate skills. It suggests that real artists start with perfect lines and end with masterpieces.

I’ve seen hundreds of students frozen by this blank page intimidation, pencils hovering uselessly above paper, afraid to make that first mark.

Here’s what I tell them: the page isn’t blank until you draw on it. Once you make that first scribble, it’s no longer empty—it’s begun. And beginning imperfectly is infinitely better than not beginning at all.

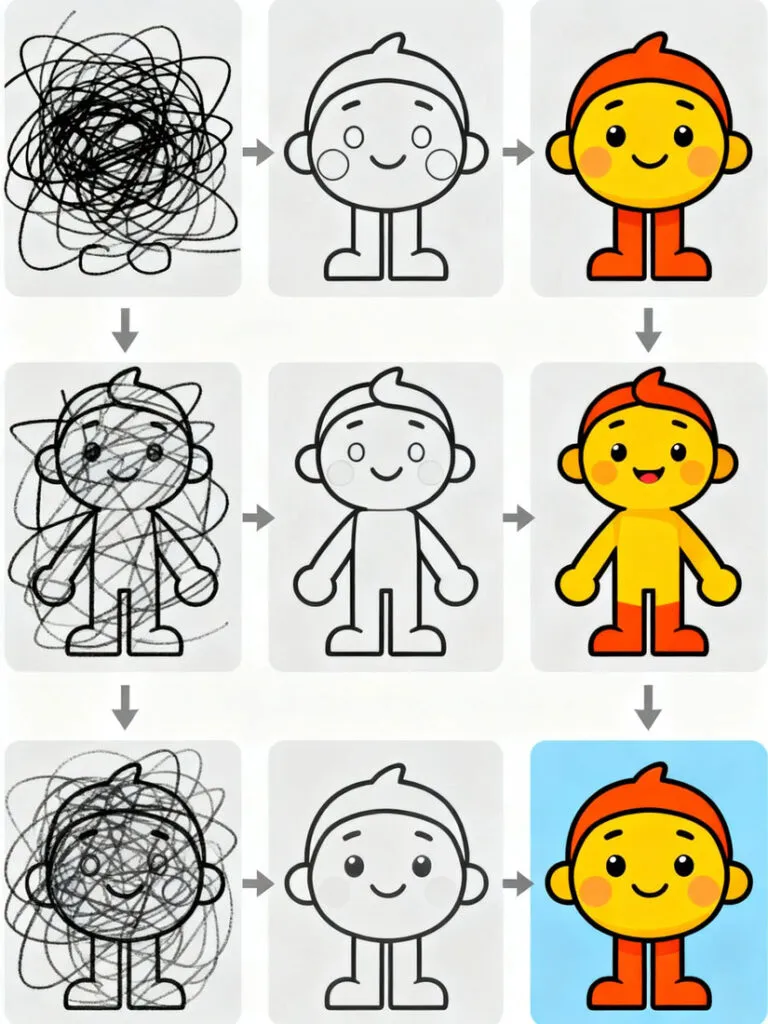

Overcoming the fear with loose scribbles

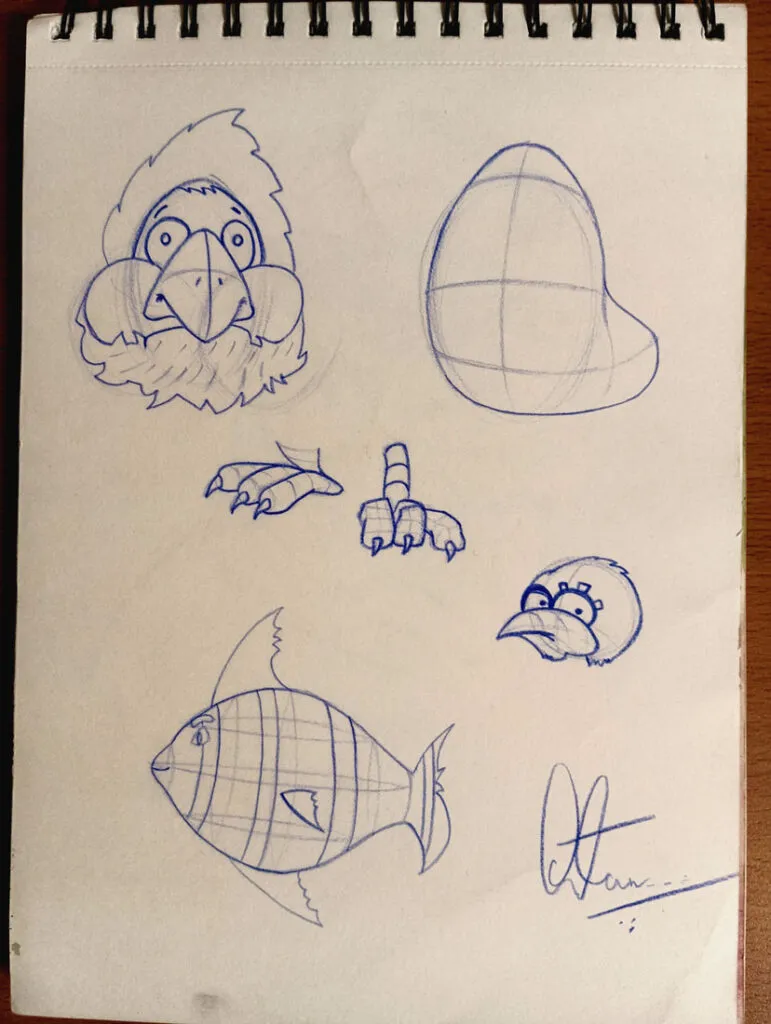

I learned this technique from an old animator who visited our studio during my first job. He’d worked on classics—actual Disney features from the 90s. I watched him start a new character design by just… scribbling.

Wild, loose circles and lines that looked like chaos. Then, gradually, he’d start seeing shapes within the scribbles. An oval here that could be a head. A curve there suggesting a body. Within minutes, those scribbles had transformed into a rough but energetic character sketch.

“You can’t edit a blank page,” he told me, “but you can always refine a scribble.”

Now I start every character design session the same way—thirty seconds of loose, fast scribbling. No thinking, no planning, just moving the pencil. This bypasses the perfectionist part of your brain that wants to judge every line.

By the time that critical voice catches up, you’ve already got marks on paper to work with.

How relaxed drawing leads to breakthroughs

During a particularly memorable workshop, I had students do an exercise where they had to draw while listening to music, eyes closed, just feeling the rhythm.

The results were predictably chaotic—swirls and zigzags everywhere. But then I asked them to open their eyes and find one shape in their scribbles that looked interesting. Just one.

A student named Raj found what looked like a lumpy circle with an extended curve in his mess of lines. “That could be a bird,” he said hesitantly.

Twenty minutes later, he’d turned that accidental shape into a quirky owl character with more personality than anything he’d previously drawn.

The looseness of the initial scribble had freed him from his usual rigid thinking. His owl had an energy and life that his careful, controlled drawings lacked.

That’s the paradox of good sketching: letting go of control often gives you better results than gripping tight. When you’re relaxed and playful, your hand moves more naturally, finding rhythms and shapes that your conscious brain wouldn’t have planned.

Every breakthrough I’ve had in my own work came from moments of relaxed experimentation, not careful planning.

Related Topics:

Foundations of Shape-Based Sketching

Light Lines First

Sketch shapes lightly so you can erase and adjust.

Identify ‘Anchor’ Shapes

The head is usually a circle or oval. The torso might be a rectangle or bean-shape. Limbs are cylinders or elongated ovals.

Connect the Dots

Use light guidelines to link shapes—this creates your underlying skeleton.

Refine & Flesh Out

Once your structure looks right, start defining details: facial features, clothing folds, textures.

Related Topics:

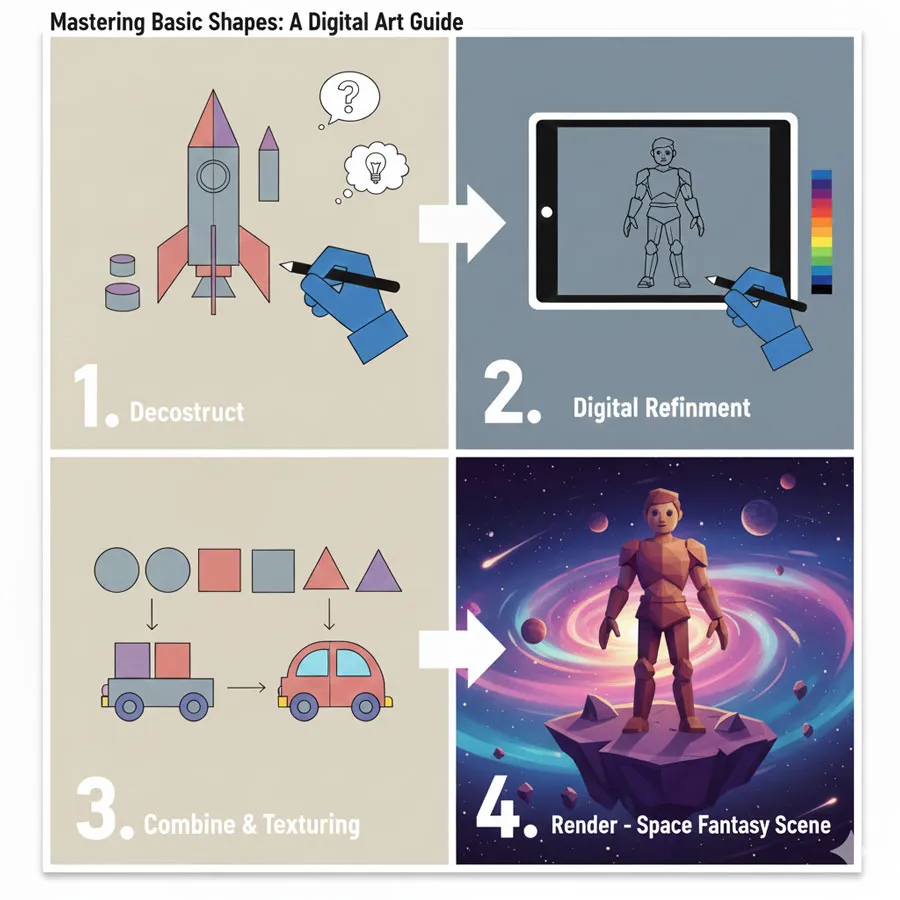

Mastering Basic Shapes

Circles: The Heart of Disney

If Disney animation had a patron saint of geometry, it would be the circle. From Mickey’s head to Baymax’s body, circles dominate the Disney aesthetic because they do something magical—they make characters feel huggable, approachable, safe.

Drawing circles by hand

Let me tell you a secret that surprises every beginner: perfect circles aren’t the goal. In fact, slightly imperfect, hand-drawn circles have more life and energy than compass-created perfection. The wobble, the slight asymmetry—these make your drawings feel organic and alive rather than mechanical and cold.

I practice circles every morning. Not because I haven’t learned them yet, but because maintaining that fluid, confident circle motion keeps my hand loose. I’ll fill a page with circles of different sizes, some fast and gestural, some slow and deliberate. Fast circles are great for initial character blocking. Slow circles work better when you’re refining proportions.

The trick to a good freehand circle is to move from your shoulder, not your wrist. Your wrist wants to create ovals because that’s how it pivots. Your shoulder can create rounder, more complete circles.

Try this: draw circles the size of your fist using just wrist motion. Now draw the same size circles while keeping your wrist still and rotating your whole arm from the shoulder. Feel the difference? That second method, once you build the muscle memory, gives you better circles with less strain.

Building characters from spheres and ovals

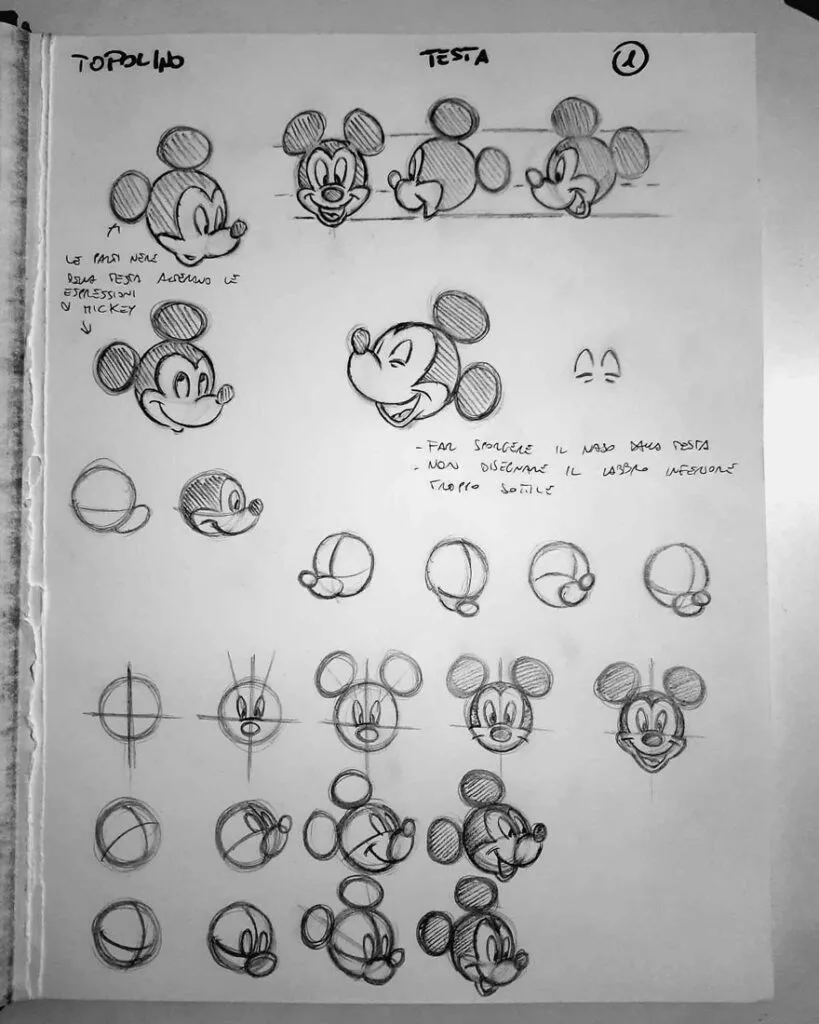

Mickey isn’t just three circles—he’s three circles of different sizes arranged in a specific relationship. Large circle for the head. Medium circles for the ears. The positioning creates immediate recognition. Too close together and he looks squashed. Too far apart and he looks alien. The relationship between shapes matters as much as the shapes themselves.

Last month, I was teaching a weekend workshop for younger students, and we spent the entire first day just playing with circles. “Draw me a character using five circles,” I’d say. Then, “Draw me a different character using the same five circles arranged differently.” By the end of the day, those kids had created mice, bears, robots, and aliens—all from the same basic circle toolkit.

The key insight is that circles can be stretched into ovals and eggs, giving you even more versatility. An oval is just a circle with direction. A vertical oval suggests height and elegance. A horizontal oval reads as width and stability. These subtle variations in circle shapes let you create endless character types while maintaining that friendly, rounded aesthetic.

Related Topics:

Squares & Rectangles: Structure and Strength

While circles get all the attention in Disney lore, squares and rectangles do the heavy lifting when you need characters that read as strong, stable, or mechanical. Every castle in Disney films starts as a collection of rectangles. Every robot, every sturdy hero, every reliable sidekick has rectangular foundations.

Building from blocks

I learned the power of squares during an exercise where I had to design a superhero using only rectangles. At first, it felt limiting—where was the grace, the flow? But as I worked, I realized the rectangles were giving my character exactly what superheroes need: power, presence, and stability. Wide rectangular torsos suggested strength. Rectangular legs implied solid grounding. Even rectangular jaws communicated determination and reliability.

Wreck-It Ralph is perhaps the best modern example of rectangle-based character design. His massive, blocky hands aren’t just visual shorthand for his video game origins—they make him read as powerful but clumsy, strong but approachable. Those rectangular proportions tell his entire story before he opens his mouth.

Using squares for proportions

Squares are secretly the most useful tool for understanding proportions. I teach students to block out characters in square units. “The head is one square. The torso is two squares tall and one and a half squares wide.” This makes scaling and proportion adjustments incredibly simple.

When students struggle with characters looking “off” but can’t identify why, I have them overlay square grids. Suddenly the problem becomes obvious—the head is 1.3 squares when it should be 1, or the arms are 2.5 squares when they should be 2. Squares turn the mysterious art of proportion into simple arithmetic. Your artistic eye still makes the final decisions, but squares give you a starting framework that prevents major errors.

Triangles: Motion and Energy

Triangles are the wild cards of shape language. They’re sharp, directional, and inherently dynamic. While circles invite hugs and squares suggest stability, triangles scream action, danger, or speed. This makes them perfect for villains, dramatic poses, and anything that needs visual energy.

Related Topics:

Dynamic gestures and poses

I remember working on a student film where we needed to redesign a villain who felt too friendly. The original design was very circular—round face, curved features. We went back to basics and rebuilt him using triangular shapes. Angular jaw. Sharp shoulders. Triangular eyebrows pointing down. Suddenly he read as threatening without changing anything about his expression or color scheme. The shapes did the work.

Triangles also create natural motion lines. A character leaning forward forms a triangle with the ground. A cape flowing behind someone creates triangular negative space. Arms raised in celebration make triangular shapes. When you want to suggest movement or energy, finding the triangles in your composition helps emphasize that dynamism.

Villains and energy

Disney villains are triangle masterclasses. Maleficent’s entire silhouette is triangular—pointed horns, angular shoulders, sweeping cape forming a triangular train. Jafar’s beard comes to a sharp point. Scar has triangular features and angular bone structure. Even Ursula, despite having an octopus body, has sharp angular features in her face and pointed fingers that create triangular gestures.

This isn’t coincidence. Triangles subconsciously read as dangerous because sharp points suggest threat. In nature, things with points can hurt you—thorns, teeth, claws. Our brains evolved to pay attention to sharp angles as potential hazards. Character designers exploit this hardwired response, using triangular shapes to create immediate visual coding that says “be wary of this character.”

Related Topics:

Turning Scribbles into Stories

One of my favorite classroom moments happens when I tell students to scribble on their page for exactly ten seconds, then stop and look at what they’ve created. In those random lines, I ask them to find one thing—any recognizable shape, any suggestion of something real. Without fail, they find something.

Finding shapes in chaos

There’s a phenomenon in psychology called pareidolia—our tendency to see patterns and familiar shapes in random stimuli. It’s why we see faces in clouds, animals in wood grain, characters in ink blots. As an artist, this tendency isn’t a bug, it’s a feature. Your scribbles contain infinite potential characters waiting to be discovered.

I’ve developed an exercise I call “Scribble Safari.” Students scribble for thirty seconds with their non-dominant hand, creating genuine chaos. Then they rotate the page, looking at it from all angles, hunting for shapes. Someone finds a profile view of a face in the curves. Someone else sees a bird’s wing. Another discovers what looks like a rounded creature body.

The magic is what happens next. They start emphasizing the shapes they’ve found, darkening certain lines, adding details that bring out the character they’ve discovered. What started as random noise becomes intentional design. This teaches a profound lesson: creativity isn’t always about planning everything first. Sometimes it’s about responding to happy accidents and being willing to follow where your scribbles lead.

The classroom “Turn this squiggle into a hero” challenge

Last semester, I drew a random squiggle on the board—just a weird, looping line that went nowhere in particular. “This is now a hero character,” I announced. “You have fifteen minutes.” The groans were audible. How could that random line be anything?

But within minutes, the room filled with creative energy. One student saw the loop as a character with an enormous pompadour hairstyle. Another recognized a curved nose in profile. Someone turned the whole thing sideways and made it a character’s unusual slouched posture. Every single student found something different in that same squiggle, and every resulting character had more personality than most carefully planned designs.

This exercise destroys the myth that good character design requires perfect planning from the start. Sometimes the best characters emerge from dialogue between accident and intention, between what you planned and what the paper suggests. The squiggle doesn’t limit you—it gives you a starting point that bypasses your usual defaults and habits.

Related Topics:

Character Creation: Step-by-Step

Stage 1: Finding Shapes

When I start designing a character, I don’t think about what they’ll look like when finished. I think about what shapes, I want to be there. Is this a friendly character? Then circles need to dominate. A strong leader type? Squares and rectangles. A mischievous trickster? Triangles with some circular softness.

The one-minute sketch

Set a timer for sixty seconds. In that time, block out your character using only basic shapes. Don’t worry about details, don’t think about whether it’s “good”—just establish the relationship between circles, squares, and triangles that feels right for your character’s personality.

I do this every single time I design characters, even after years of experience. That one-minute sketch captures energy and essence that’s easy to lose when you get bogged down in details later. Sometimes I’ll do five or six one-minute sketches, each exploring a different shape balance, before choosing which direction feels strongest.

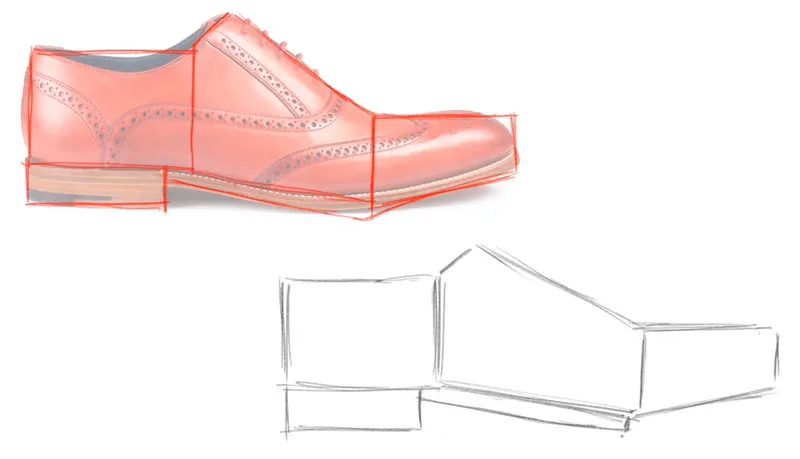

Overlaying structure

Once you have your loose scribbles or rough shapes, the next step is finding the underlying geometric structure. Draw clean circles, squares, and triangles over your rough marks, identifying the core shapes. This is like finding the skeleton beneath the skin.

I teach students to use different colored pencils for this. Blue for initial scribbles, red for the clean geometric structure. This color-coding makes it obvious where the structure lives within the chaos. Often, you’ll discover that your instinctive scribbles already contained good proportions and relationships—your hand knew things your brain hadn’t consciously planned.

Related Topics:

Stage 2: Building Personality

Here’s where shape language becomes powerful. Two characters built from identical shapes can have completely different personalities based on the size relationships and proportions you choose.

Big vs. small shapes for emotion

A huge circular head on a tiny rectangular body reads as comic relief—think Olaf from Frozen or any number of Disney sidekicks. The proportion imbalance creates instant comedy. But reverse it—tiny head on massive body—and you get something that reads as either strong and possibly dim-witted (like the Yeti from Monsters Inc.) or intimidating (like Gaston’s exaggerated muscular build).

Medium-sized heads on medium-sized bodies read as “normal” protagonists. Slightly enlarged heads suggest youth or innocence. Extremely small heads can read as elegant or aristocratic. These aren’t rules—they’re tendencies our visual culture has established. But understanding these tendencies gives you a vocabulary for communicating character traits through pure proportion.

Expression through shape placement

During an advanced character design class, I had students create three versions of the same character showing different emotional states using only shape position and size—no facial features allowed. Fear? Shapes compressed together, rounded for defensiveness. Confidence? Shapes spread out, with strong triangular elements. Sadness? Shapes drooping downward, with heavy rectangular elements suggesting weight.

The results were remarkably effective. Even without eyes, mouths, or any traditional expression indicators, the pure geometric compositions communicated emotion clearly. This taught everyone a vital lesson: if your shape language is strong, everything else you add—details, expressions, colors—amplifies that foundation rather than trying to create personality from scratch.

Related Topics:

Stage 3: Defining Details

Now comes the most dangerous phase of character design—adding details. Dangerous because this is where many artists ruin the energy and clarity of their initial shape work. The temptation is to add more and more, believing that detail equals quality. Usually, the opposite is true.

How every detail enhances shapes

Good details serve the underlying shapes. Mickey’s gloves aren’t just white hands—they’re rounded, reinforcing his circular design language. His shoes are large and rounded, echoing the friendly circle theme. Even his buttons (when he wears them) are circular. Everything supports the core shape vocabulary.

When I’m adding details, I constantly check that each addition serves the shape language. Designing a triangular villain character? Then their jewelry should have sharp points. Their buttons should be angular or sharp-edged. Their clothing should have triangular hems and pointed collars. Every detail either reinforces your shape language or fights against it. Fighting against it creates visual confusion.

Keeping lines alive

Here’s something I wish someone had told me when I was starting: perfect, clean lines often have less energy than rough, confident ones. When students over-work their drawings, cleaning up every little wobble, they often squeeze the life out of their characters. The characters become stiff and dead.

I learned this watching old Disney animation sketches. The rough pencil tests, before they were cleaned up, had incredible energy and life. The clean versions were technically perfect but had lost some of that raw vitality. Modern character designers understand this—many keep intentional roughness in their line work to maintain that alive, energetic feeling.

When finishing a character sketch, I leave some construction lines visible, keep some line weight variation, and don’t stress about every curve being perfect. That imperfection reads as humanity, as spontaneity, as something created by a hand rather than a computer. It’s the difference between a character that feels ready to move and one that feels frozen in time.

Related Topics:

- Step by Step guide for Retro 3D Movie Effect in Photoshop

- Starting CorelDRAW

- How to Add Falling Snow in Photoshop

Character Walkthroughs

Woody (Toy Story)

- Head & Hat

- Draw a large oval for the head.

- Place a slightly flattened oval on top for the brim of his cowboy hat.

- Torso & Vest

- Under the head, a tall rectangle (slightly curved inward at the waist).

- Add a smaller rectangle on the chest for the vest.

- Arms & Legs

- Cylinders for upper arms and thighs.

- Taper them toward the wrists and ankles.

- Hands & Boots

- Use circles for palms; add finger-guidelines.

- Boots start as trapezoids, rounded at the toes.

- Features & Clothing

- Mark center lines on the face to place eyes, nose, and mouth.

- Sketch cow-print on vest and buttons.

- Refinement

- Erase extra guides, thicken final lines, add stitching details and folds in fabric.

Related Topics:

- How to Create Silver Metallic Effect in Illustrator

- How to Create Rain Effect in Photoshop

- CryptoTab – Bitcoin Miner

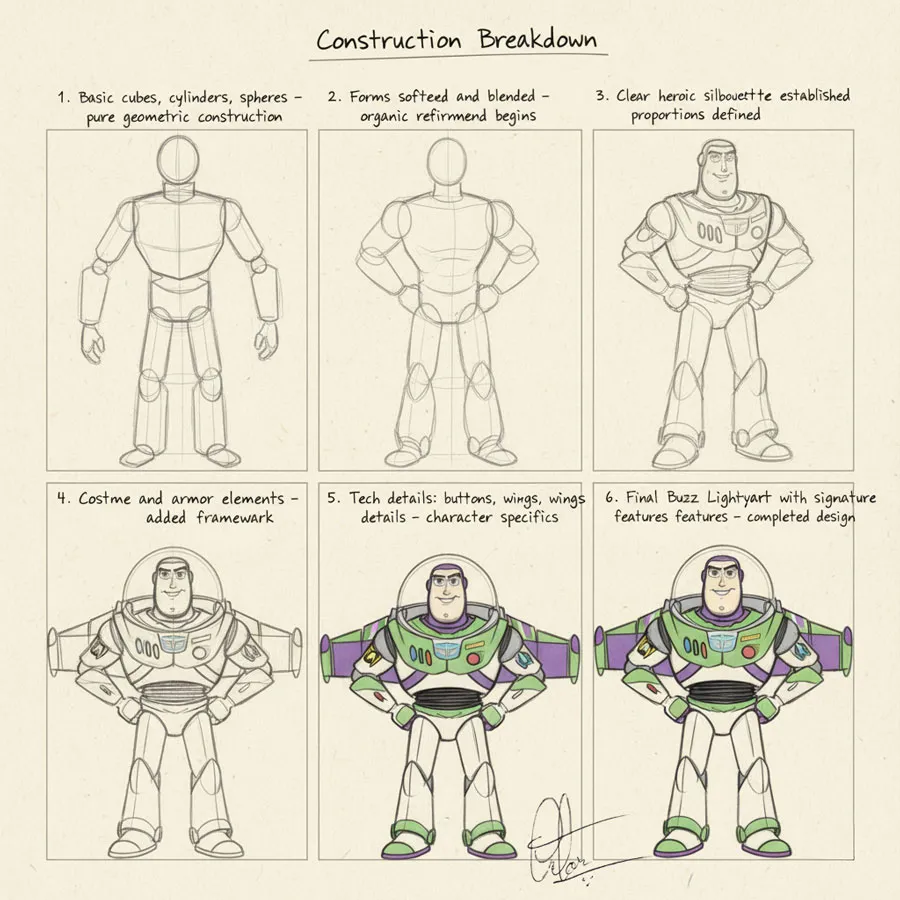

Buzz Lightyear (Toy Story)

- Helmet & Head

- Large circle for the helmet.

- Inside, an oval for his head, leaving space for the transparent dome.

- Chest & Jetpack

- Broad rectangle (like a thick book) for the torso.

- Add rounded rectangles on shoulders for armour panels.

- Limbs

- Arms and legs as connected cylinders—note the segmented armour.

- Joint circles at elbows and knees help you bend them.

- Utility Details

- Draw rectangle “buttons” on his chest.

- For the jetpack, sketch a boxy cylinder behind the torso.

- Final Touches

- Refine visor edges, belt and glove details, and add the Star Command logos.

Related Topics:

Mickey Mouse

- Head & Ears

- Draw one large circle.

- Add two medium circles overlapping the top for ears (the classic silhouette!).

- Face Guidelines

- A vertical centre line and horizontal eye line inside the head circle.

- Body & Limbs

- Pear-shape for torso.

- Limbs as simple cylinders, with circles for hands and feet.

- Outfit Details

- Circle-buttons on shorts.

- Glove lines, shoe curves.

- Polish

- Erase guidelines, thicken outlines, add that signature grin.

Related Topics:

Refining Your Sketch

- Line Weight: Press lightly on structural lines, heavier on outlines and important folds.

- Erase with Intention: Remove only the guide shapes you no longer need.

- Add Depth: Light shading along curves and overlaps—think where the light hits.

- Textures & Patterns: Cowboy vest prints, car decals, or fabric stitch marks.

Mistakes New Artists Make

Overcomplicating before mastering shapes

The biggest mistake I see repeatedly is students trying to draw complicated characters before understanding simple ones. They want to design an elaborate fantasy creature with scales, wings, horns, and armour before they’ve mastered how to construct a simple mouse from circles.

I had a student named Arjun who was obsessed with dragons. Every assignment, he’d try to draw elaborate dragons with complex anatomy and intricate details. They never quite worked—proportions felt off, poses looked stiff. Finally, I convinced him to spend one full week drawing only with circles, squares, and triangles. No dragons. Just shapes.

He was frustrated at first, feeling like he was going backward. But by the end of the week, something had clicked. When he returned to his dragons, they suddenly had structure and clarity they’d lacked before.

He’d learned to see the basic shapes underlying complex forms. His dragons became constructed from spheres for body segments, triangles for wings and spines, cylinders for necks and limbs. They went from muddy and confused to clear and powerful.

Fear of ugly lines

New artists want every line to be beautiful. So they draw slowly, carefully, tentatively—and produce stiff, lifeless work. Beautiful lines come from confident motion, and confidence requires being willing to make ugly marks.

During life drawing sessions, I make students do warm-up exercises where they have to draw fast and loose for five minutes before doing any careful work. Those warm-up drawings are often “ugly”—gestural, rough, sometimes barely recognizable. But they’re alive. And more importantly, they get the fear of making bad marks out of students’ systems.

“You’ll draw thousands of ugly lines in your career,” I tell them. “The sooner you make peace with that, the sooner you’ll draw beautiful ones.” The ugly lines are practice. They’re exploration. They’re the necessary mess that comes before clarity. Artists who can’t tolerate ugly lines never develop the loose, confident mark-making that defines professional work.

The breakthrough moments

I keep a folder of student work from semester beginnings and semester ends. The transformation is always dramatic. First-week drawings are typically tight, overworked, and lifeless. Final-week drawings are loose, confident, and energetic. The change isn’t some mysterious talent emerging—it’s fear dissolving.

One of my proudest teaching moments was watching a student named Meera go from being unable to draw circles without rulers to confidently blocking out characters in minutes. Her breakthrough came during a particularly chaotic class where we were doing rapid-fire character designs—two minutes per character, no thinking, just doing.

By the tenth character, Meera stopped analyzing and started flowing. Her hand moved confidently, her shapes were clear, and most importantly, she was smiling. “I’m not thinking anymore,” she said, delighted and surprised. “My hand just knows what to do.” That’s the breakthrough—when conscious effort gives way to unconscious competence, when the shapes become intuitive rather than intellectual.

Related Topics:

Tips for Consistency & Style

- Use a Lightbox or Window: Trace your basic shapes on a second sheet once you’re happy with proportions.

- Keep a Shape Library: Practice drawing perfect circles, ovals, and rectangles freehand—muscle memory helps enormously.

- Study Silhouettes: A strong silhouette makes the character instantly recognizable even in solid black.

- Reference Often: Have a still image of your character nearby to catch subtle details.

Drawing Practice Exercises

The Shape Challenge

Take any Disney character—Mickey, Donald, Goofy, Elsa, whoever you love. Now draw them using only one shape. Just circles, or just squares, or just triangles. This forces you to think about how far you can push a shape while maintaining character recognition.

I’ve seen students create incredible Mickey variations this way. All-square Mickey becomes surprisingly geometric and almost art deco. All-triangle Mickey gets edgy and modern. These exercises break you out of assumptions about how characters “must” look and train you to think flexibly about shape application.

Try this extension: draw the same character happy using circles, angry using triangles, and calm using squares. You’ll discover how profoundly shapes influence emotional reading, even before you add facial expressions.

The Scribble-to-Character Game

This works beautifully for group practice or solo experimentation. Close your eyes, scribble for ten seconds with your non-dominant hand. Open your eyes, rotate the paper to all four orientations, and force yourself to find a character in those marks. Give yourself fifteen minutes to develop what you’ve found.

I play this game at the start of every personal sketching session. It defeats my perfectionism and gets me into a playful, exploratory mindset. Some of my favorite personal character designs came from this exercise, discovering shapes and personalities I never would have consciously planned.

The group version is even better. Everyone scribbles, then passes their paper to the person next to them. That person has to find and develop a character from someone else’s random marks. The results are always surprising, often hilarious, and frequently brilliant.

Quick Memory Exercise

Close your eyes and imagine a character—any character, real or imagined. Hold that image in your mind for thirty seconds, noting what shapes dominate. Now, without opening your eyes, sketch those basic shapes from memory. Open your eyes and refine.

This exercise trains your ability to see shapes rather than complex details. When you recall a character from memory, you don’t remember every detail—you remember their essential shape relationships. This is exactly what you need to capture when designing or drawing characters.

I do this with famous characters, asking students to draw them purely from memory using only basic shapes. The results are never accurate reproductions—but they’re almost always identifiable, because the shape relationships are what create recognition, not the details.

Related Topics:

Next Steps & Practice Drills

- 30-Day Character Challenge

- Draw one basic shaped Disney character per day.

- Mix & Match

- Swap shapes between characters (e.g., give Buzz McQueen’s wheels!) to build adaptability.

- Timed Sketches

- Set a 5-minute timer to block in shapes quickly, then refine in another 5.

Related Topics:

Inspiration: Disney’s Secret Formula

“Every legendary character you love started as a humble circle or rectangle. With each simple shape you draw, you’re stepping into the very shoes of the animators who created these icons.”

Keep your pencils sharp and your imagination sharper. Before you know it, you’ll be not just copying Disney magic, but inventing your own.

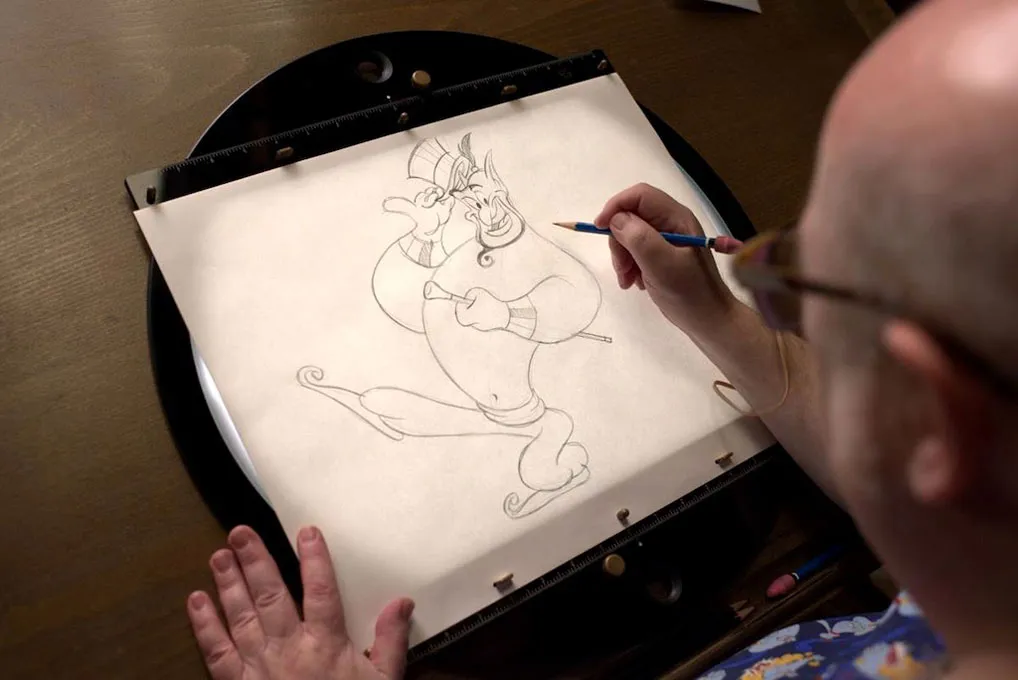

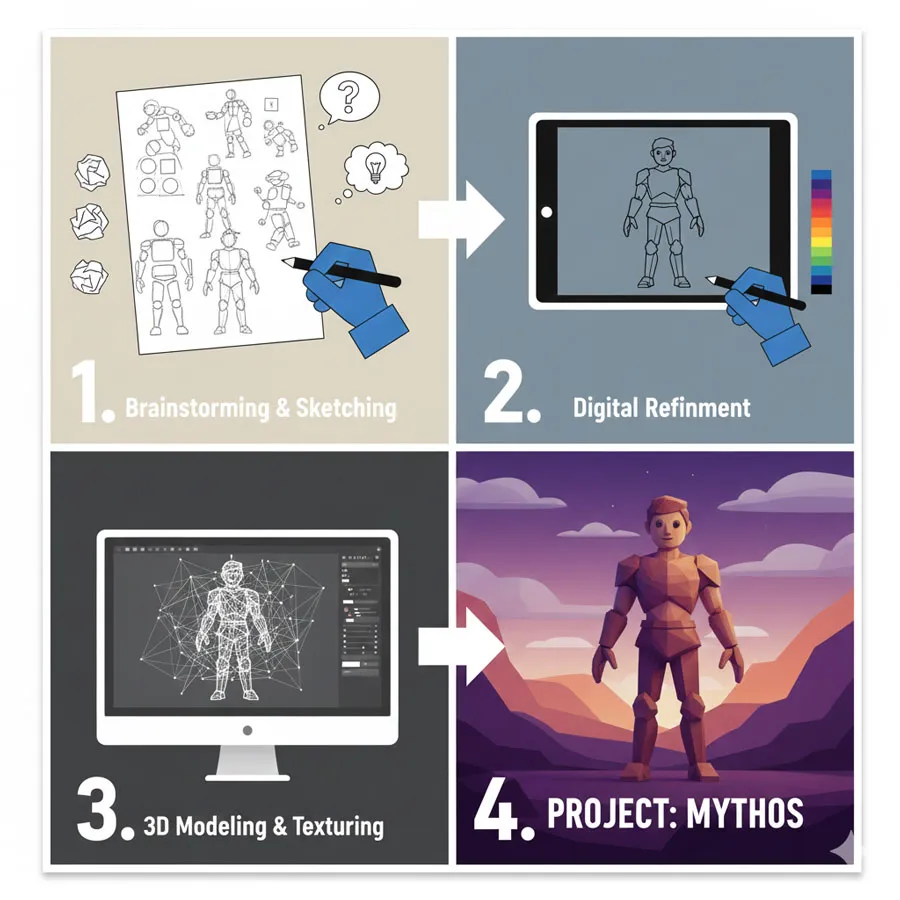

How animators use shapes at every step

Even in modern Disney and Pixar films, where everything is rendered digitally, the animation process still begins with shape blocking. Artists don’t start by modeling detailed characters in 3D software. They start with rough shape sketches, sometimes called “silhouette tests,” where they make sure the character reads clearly as a collection of basic forms.

The Inside Out characters are perfect examples of this modern shape language. Joy is primarily circular—round face, bouncing movement, curved dress silhouette. Sadness is teardrop-shaped, suggesting weight and gravity. Anger is rectangular and compressed like a pressure cooker. Fear is stretched and angular. Disgust has sharp, triangular elements. Before any details were added, these characters’ shapes communicated their personalities.

Evolution from early sketches to modern animation

The earliest Disney sketches reveal something fascinating: the fundamentals haven’t changed. Looking at Ub Iwerks’ original Mickey drawings from the 1920s, you see the same circle-based construction modern animators use today. The technology has transformed completely—from hand-drawn cells to computer animation—but the underlying shape language remains constant.

Walt Disney famously said, “I don’t make films primarily for children. I make films for the child in all of us.” That philosophy extended to character design. Simple shapes communicate universally because they tap into pre-verbal, pre-cultural pattern recognition. A circle is friendly whether you’re five or fifty, whether you’re watching in America or Japan or Brazil.

Advice from Disney legends

Glen Keane, the animator behind Ariel, Beast, and Aladdin, often talks about the importance of simple shapes in complex characters. Beast, despite being covered in fur and complicated details, is built from basic shapes—circular head, rectangular torso, triangular lower body creating weight and power. “The shapes come first,” Keane has said. “Everything else is decoration.”

Andreas Deja, who animated Jafar and Scar, emphasized that villains need strong, clear shapes more than heroes do. “A villain has to read instantly,” he explained in an interview. “You don’t have time for subtle character development. The shapes have to scream their personality immediately.” That’s why Disney villains are often the most geometrically pure characters in their films—no ambiguous shapes, just clear, sharp design language.

Related Topics:

- Breaking Down Creative Barricades

- Creativity is a Journey not Destination

- How to Recolor Artwork in illustrator

Conclusion

It’s been more than twenty years since I stared at that animation book and realized Mickey Mouse was just three circles. Since then, I’ve drawn thousands of characters, taught hundreds of students, and worked on more projects than I can count. And I still start every single character the same way—with basic shapes.

The journey from doodles to Disney-quality work isn’t about acquiring some mysterious artistic talent. It’s about training your eye to see the simple geometric forms underlying complex appearances. Every legendary character in animation history began as someone playing with circles, squares, and triangles, discovering which combinations created magic.

Your scribbles aren’t failures—they’re explorations. Your rough circles aren’t mistakes—they’re foundations. Every uncertain line you draw is practice for the confident ones coming soon. The more you play with basic shapes, the more naturally they’ll flow from your pencil. What feels mechanical and thought-intensive now will eventually become intuitive and effortless.

I think about my student Priya, who came into class convinced she couldn’t draw, and left designing her own characters. I think about Meera, whose hand learned to move confidently once her mind stopped interfering. I think about every student who discovered that the barrier between them and their favourite Disney characters wasn’t talent—it was just understanding how to see and use shapes.

You’re not starting from nothing. You already know circles, squares, and triangles. You’ve known them since childhood. Now you’re just learning to see them everywhere, to build with them, to use them as your vocabulary for visual storytelling. Mickey Mouse, drawn by a master animator or by a beginner following shape principles, is still fundamentally three circles. The magic isn’t in drawing perfect circles—it’s in understanding that those circles can become anything.

So grab your pencil. Draw some loose scribbles. Find shapes in the chaos. Build characters from circles, squares, and triangles. Make mistakes, draw ugly lines, and keep going. Every Disney legend started exactly where you are now—with basic shapes and the willingness to play.

Your legendary characters are waiting. They’re already there in your next circle, your next square, your next triangle. You just have to be brave enough to put them on paper and see where they want to go.

Now go create something magical.

Related Topics:

- How to Create Flower using Gradient Mesh in Illustrator

- How to Create Metallic effect in Illustrator

- How to Create A Pressure Sensitive Brush in Illustrator

- How to set Brush Pressure in Illustrator

- How to design a Retro Flower Pattern

- How to make a Semicircle in Illustrator

- How to use Mesh Tool in illustrator

- How to use Gradient Tool in Illustrator

- Wolverine

- Kai Hiwatari